Amazon took advantage of tax laws that allowed online retailers to avoid collecting sales tax to create a pricing advantage. Now, Temu has a pricing advantage created by not paying customs duties and/or taxes.

Amazon didn’t have to collect sales tax because it sold in most states without physical presence, also known as “nexus.” Any retailer was obliged to collect from shoppers only if it had a substantial physical presence in their state. This principle was established by the Quill Corp. v. North Dakota case in 1992. In an interview with Fast Company in 1996, Jeff Bezos explained why he incorporated Amazon in Washington: “It had to be a small state. In the mail-order business, you have to charge sales tax to customers who live in any state where you have a business presence. It made no sense for us to be in California or New York.”

Without having to charge sales tax, Amazon could offer lower prices than local retailers that couldn’t evade it. Amazon kept that advantage for decades, and it was instrumental in making people shop online — goods were often cheaper. Other online retailers, of course, also benefited from the same conditions.

Then, over many years, court cases, proposed laws, and changes, Amazon went from collecting no sales tax to collecting it in its growing nexus states (it was by then in many of them due to building warehouses), to all states and, finally, for its third-party sellers. Today, everything sold on Amazon is charged sales tax in the U.S.

By the time Amazon couldn’t evade charging sales tax anymore, it had grown big enough that it didn’t need to rely on the loophole. It went from fighting states to avoid tax collecting to lobbying for it. Products lost some price advantage, but Amazon didn’t lose shoppers it spent years courting.

Temu, which avoids paying customs duties because most orders fall below the de minimis threshold ($800 in the U.S.), is repeating Amazon’s playbook. It can sell goods for less because it ships customer orders directly from China rather than importing goods in bulk like Amazon or Walmart. It doesn’t pay any customs duties when it does that. The loophole and, thus, the price advantage will inevitably close. Perhaps sooner in some countries than others, as all are moving to change or remove the threshold level altogether. For now, even Amazon is vying to benefit from it.

But by the time Temu can no longer rely on the de minimus loophole, it likely would have grown past it. It’s not going to be the door to slam shut on Temu. Like Amazon, Temu would have used the advantage to grow but not rely on it anymore when it lost it. Products on Temu have already become more expensive since its launch as it relies less on shockingly low prices, and 20% of Temu’s sales now come from local warehouses — all of which already pay customs taxes.

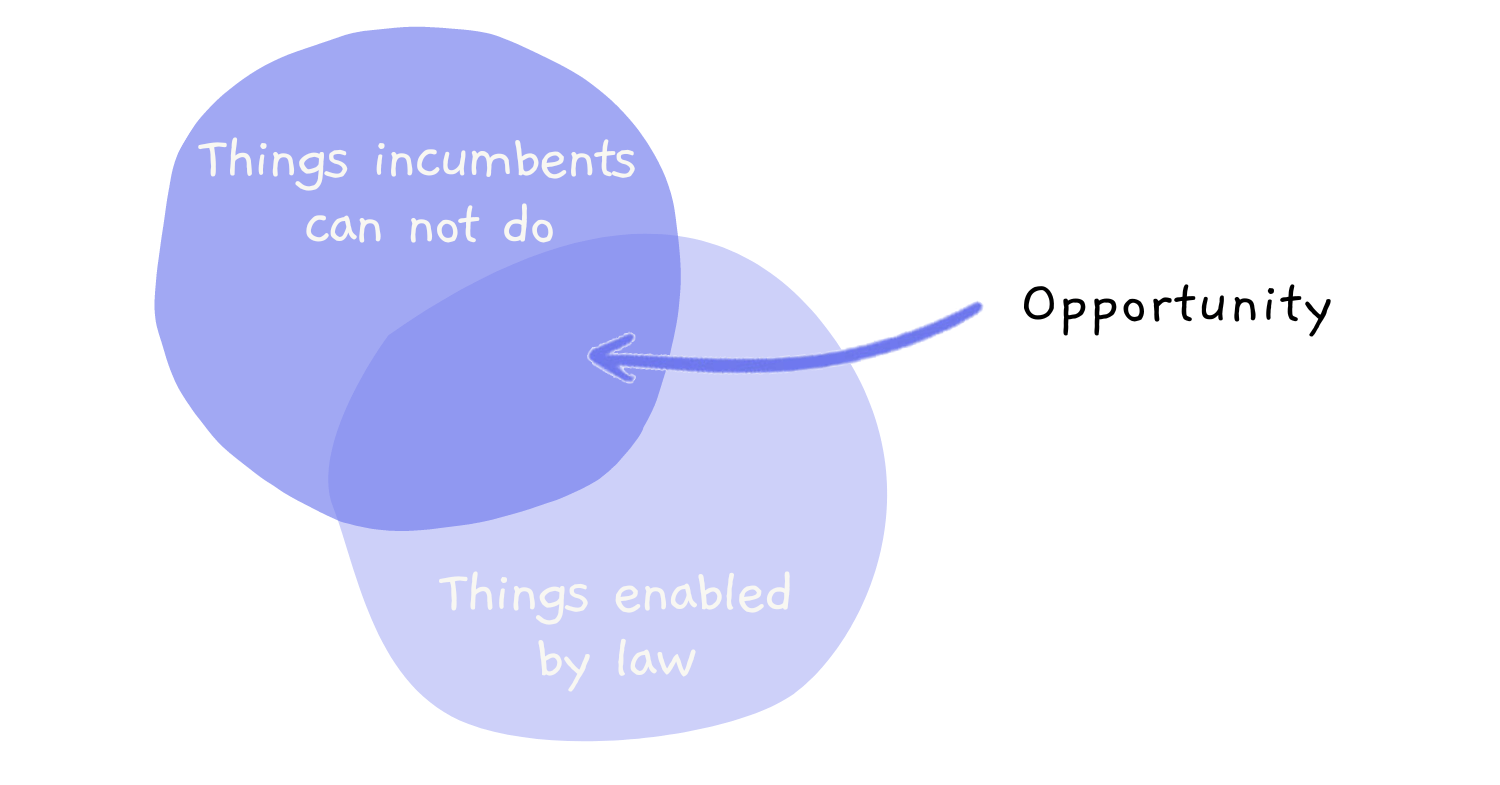

Amazon and Temu used regulatory opportunities with expiration dates to create an advantage that powered their growth. In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a decades-old tax ruling that had allowed many internet retailers to avoid charging sales tax. Two years later, most states also got Amazon to collect sales tax on behalf of third-party sellers. As the door shut on Amazon, a new one opened for Chinese retail apps. In 2016, the United States increased its de minimis threshold from $200 to $800. A few years later, Shein started to take off, and then, in 2022, Temu launched.