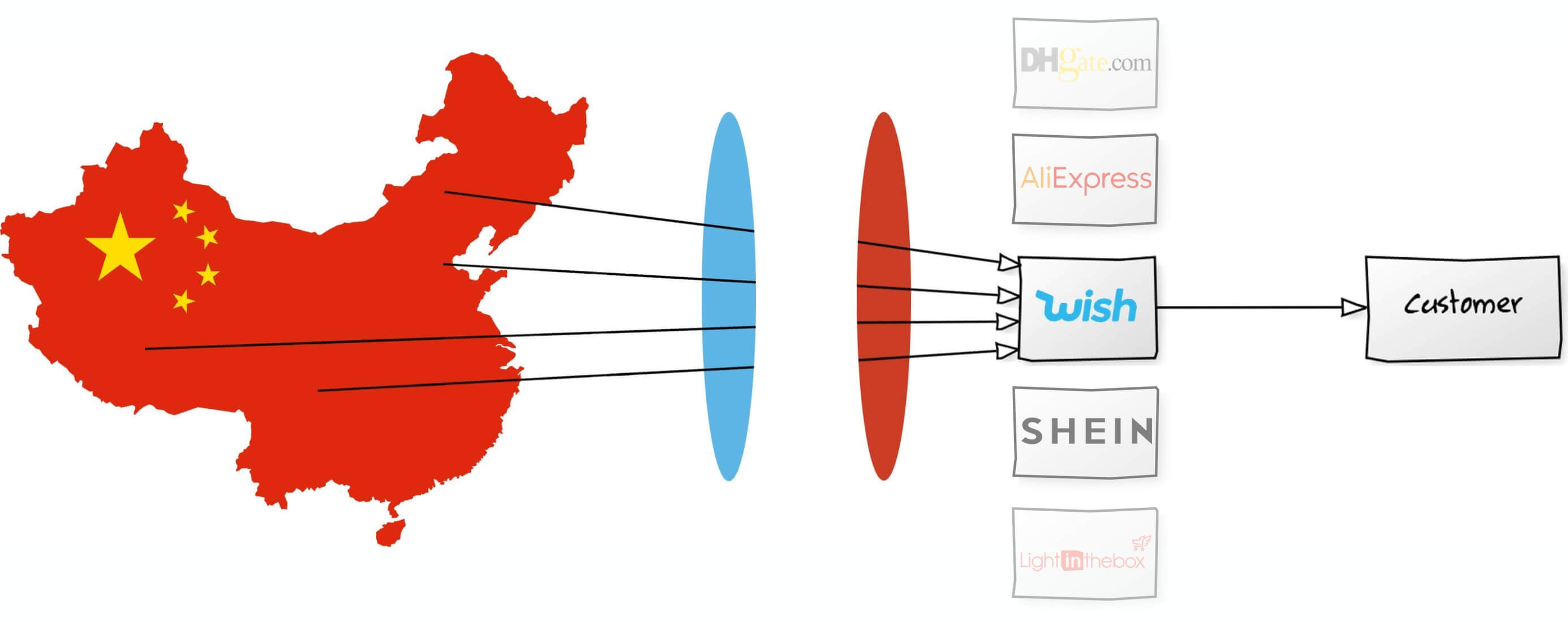

Every year at least tens of billions of dollars worth of goods are sold directly from China to consumers in the US and elsewhere. Without the excitement, attention, and venture capital other parts of e-commerce have received, it is this quiet industry capturing the profits. It didn’t exist before 2010.

In the 2010s, AliExpress and Wish launched, and most recently, Joom. A few years before that, DHgate, SHEIN, LightInTheBox opened but started to see significant growth only in the last decade. They are either Chinese online retailers sourcing from local factories or marketplaces consisting of China-based sellers. They don’t sell in China.

The businesses that sell through those platforms are small companies, rarely backed by capital, and mostly focused on producing a single line of products. They typically don’t have an Instagram following - or an account at all - but they do have profits. Enough to keep them running. The platforms do most of the work of attracting customers and matching them with the selection of products.

Individually, those businesses are boring. As a whole, they represent an invisible but significant part of e-commerce. Yet the model is simple - they make products consumers want at price points they are willing to pay and at quality worth the price.

“Why buy a $40 bikini made in America when you can buy a $4 bikini directly from China? For that matter, why buy a $20 bikini made in China but imported by a US company like the Gap when you can buy a $4 bikini directly from China?” in 2018, Alana Semuels wrote for The Atlantic.

Services like Wish or SHEIN, and others, are mostly unknown to anyone, but their target customer base. Nor the companies behind them are often in the crosshairs of the press. Their founders are mostly incognito, too. Both of those apps are consistently in the top 10 most-downloaded shopping apps on both iPhone and Android app stores, however.

“I think people misunderstand the demographics of this country and places like Europe,” Peter Szulczewski, CEO and co-founder of Wish said in an interview, referring to the millions of shoppers who find value on Wish.

AliExpress has over 440 million monthly visitors. Wish adds 100 million, SHEIN 50 million, and DHGate 25 million. There are dozens of other websites. Combined, they almost equal eBay’s traffic. eBay sold more than $85 billion worth of products last year. AliExpress and the rest do not combine to GMV matching that of eBay’s, but the total is in the same order of magnitude.

According to SCMP’s Chinese news site Abacus, SHEIN’s sales amounted to $2.83 billion in 2019. Estimates put Wish at above $10 billion GMV. And AliExpress is aiming to reach $10 billion GMV by 2022-2023 in Russia alone, according to Reuters, citing the CEO of the company Dmitry Sergeev.

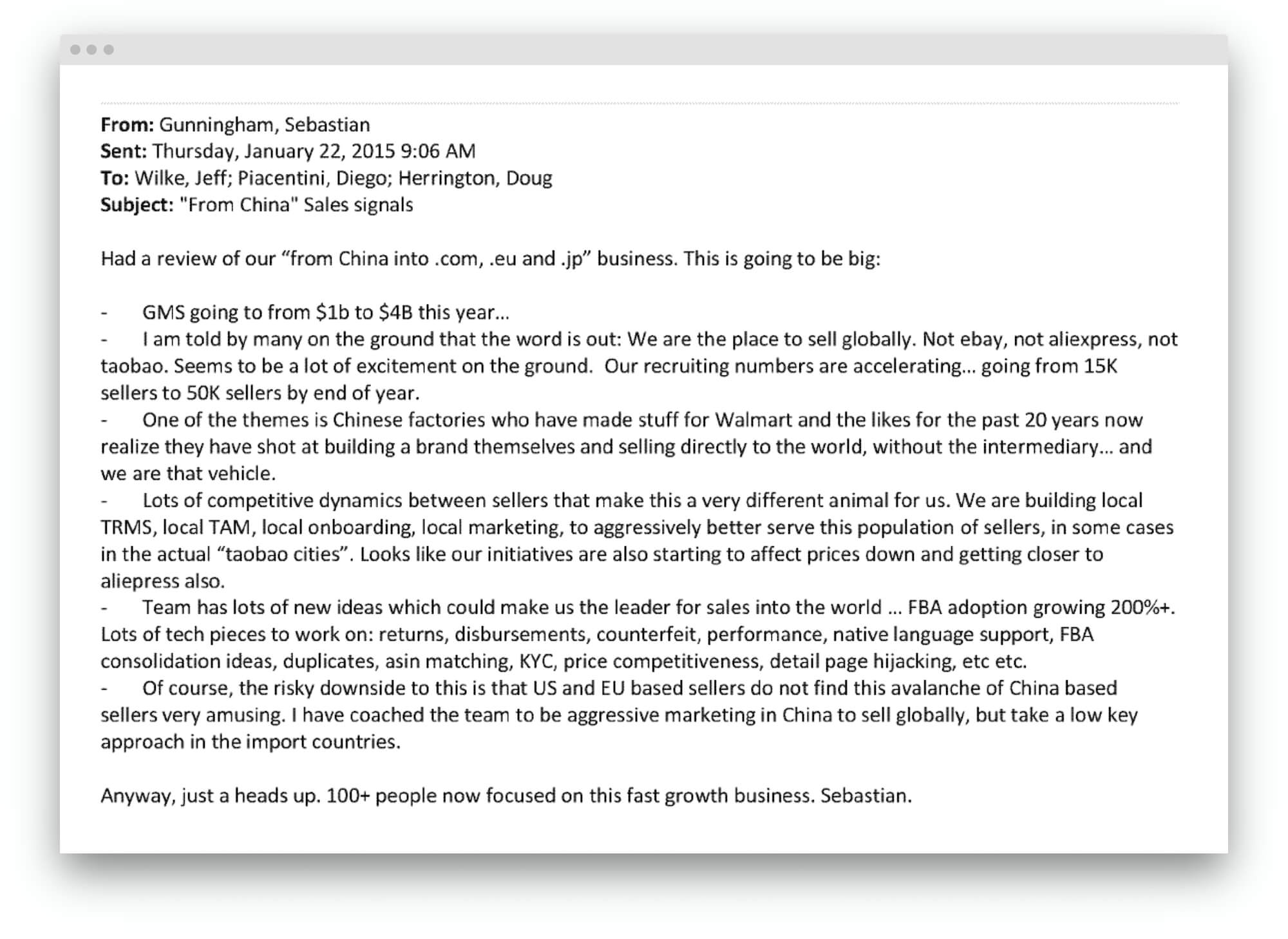

“One of the themes is Chinese factories who made stuff for Walmart and the likes for the past 20 years now realize they have shot at building a brand themselves and selling directly to the world, without the intermediary… and we are that vehicle.” Wrote Sebastian Gunningham, senior vice president of Amazon Marketplace at the time, in an internal email from 2015 recently released by the House Judiciary Committee.

Sebastian Gunningham started the email with “this is going to be big.” In 2019, Amazon global GMV was $335 billion. $200 billion of which was by the marketplace sellers, many of which are now China-based. Tens of billions of dollars of that GMV are by those companies from China. According to the email, China-based GMV was just $1 billion in 2014.

The critical insight was that factories that previously produced products for retail giants like Walmart realized that e-commerce platforms allowed them to reach consumers directly. “Let’s cut out the middleman,” said Geoffrey Stewart, an Amazon employee in Shenzhen, at a 2019 April trade event in Hong Kong in a video the Wall Street Journal viewed. “We think that will enhance margins for our manufacturing partners, and it will delight customers.” Although by removing intermediaries, Amazon lost many of the checks in the supply chain created by them. Amazon wasn’t the only platform that allowed that, but its Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) created a shopping experience that eliminated long delivery times often associated with buying from China.

Amazon didn’t create the market nor is alone in it, however. Its fulfillment capability offers a different experience than other direct-to-consumer from China platforms, but all do fundamentally the same.

However, the industry has serious issues: counterfeits, knockoffs, intellectual property infringement, unsafe products, missing certification, improper inspection, lack of liability insurance, tax avoidance, unaccountability of distant businesses, legal systems unequipped to police them, and more. Those issues affect consumers and put domestic retailers at a disadvantage. While only a small number of consumers notice them, it is often harder to find a legal remedy when they do.

Many countries are starting to undo some of the things that allowed this market to launch. For example, the subsidized shipping from China that allowed small packages to be often shipped cheaper than shipping the same package domestically. Universal Postal Union, an arm of the United Nations that has governed international shipping rates for over a century, slashed the subsidy on July 1st, doubling shipping costs overnight.

Few realize this market exists, yet, measured by sales volume, the 2010s were the decade of direct-to-consumer from China. The next decade appears to be bringing changes like import tariffs, shipping rate increases, and an updated approach to product safety. However, the demand for those goods is not going away.