Recent months have highlighted the vulnerability that stems from Amazon’s fulfillment operations: Amazon warehouses and ships practically everything sold on Amazon. That includes products sold by the company and its vast marketplace because most of the third-party sellers rely on Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA). The same FBA moat that allows the company to provide a consistent shopping experience despite millions of sellers behind the scenes is a single point of failure. As it tries to protect that single point of failure, it needs increasingly strict quantity restrictions, high fees, and complex rules for sellers using FBA.

When it breaks, as it did during the pandemic, the whole Amazon breaks. “We typically want to sell as much as we can, but our entire network is so full right now with just hand sanitizers and toilet paper that we don’t have the capacity to serve other demand,” said an Amazon employee involved in changes that saw the company remove like deals and recommendations, a step it had never taken before.

This week, Amazon started preparing its warehouses for the holidays. “Even though it’s July, we’re preparing early for the holiday season to meet sustained increased demand,” the company wrote to sellers in an email, which included new restrictions. Holidays regularly test Amazon’s fulfillment capacity, often requiring temporary solutions like ad-hoc warehouses in parking lots to be built. However, more importantly, any changes highlight the company’s struggles to make the sellers adapt to the new fulfillment necessities.

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) was launched nearly fourteen years ago, on September 19th, 2006. It’s a service that allows sellers to offload warehousing, shipping, and handling of returns to Amazon. The service contributed a large part of the $53.76 billion in seller fees the company collected in 2019. Crucially, however, it allows the company to offer a consistent experience to Prime members. “We created Fulfillment by Amazon because it is good for Amazon.com customers, and therefore, great for our third-party sellers,” said Joe Walowski, Product Manager at Fulfillment by Amazon, when announcing the service.

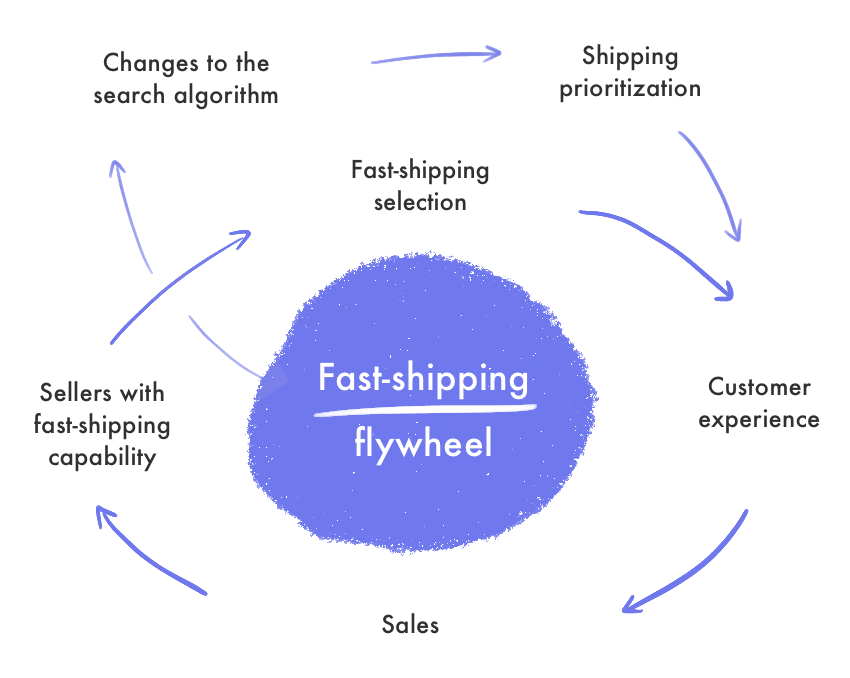

The service is hugely popular because it powers the fast shipping flywheel on Amazon. This economic engine incentivizes sellers to improve customer experience through a greater selection of products with fast shipping. Fast shipping leads to a better shopping experience and, thus, more sales. As sellers grow sales, they add more products with fast shipping. That allows the marketplace to adjust its search algorithm to prioritize fast shipping. Changes to search ranking improve customer experience further, displaying mostly products with free and fast shipping. Feeding any part of this flywheel accelerates the loop.

The more sellers use FBA, the more selection with fast shipping there is, the better the customer experience becomes, which leads to more sales for those sellers and more Prime members for Amazon.

When FBA first launched, it was merely a warehousing service that also handled fulfillment. Sellers would often store inventory for months because the fee structure (the twelve-month long term storage fee) allowed that. But as more sellers wanted to use FBA and as Amazon focused on achieving nationwide next-day delivery, the service transformed to strictly a fulfillment service. The fee structure didn’t allow for multi-month storage; instead, it incentivized storing a few week’s worth of supply.

Amazon also introduced the Inventory Performance Index (IPI) in 2018, a metric that scores the seller’s inventory efficiency. It measures excess, in-stock, and stranded inventory, and arrives at a score between 0 and 1,000 (the company doesn’t disclose the exact formula). Once a seller is below a particular threshold value, they can no longer send in more inventory. That threshold rose from the original 350 to 400 last year, and recently to 500.

The IPI metric, quantity restrictions, various FBA fees, and the fast shipping flywheel are connected. Amazon manages an increasingly large pool of warehouses - it opened 33 new fulfillment centers in the US in 2020 - that deliver to a growing number of Prime members expecting next-day delivery. That means those warehouses need to run more efficiently, and the inventory needs to move faster. Ultimately, that translates to sellers too. Efficient managing of inventory is hard, however. It takes the most experienced sellers to do that well. That is one of the key reasons why Amazon’s attempt to launch the Seller Fulfilled Prime (SFP) service - which allows sellers to offer Prime shipping without FBA - didn’t work. Most sellers failed to meet the strict on-time requirements. Amazon paused the program indefinitely. Managing FBA as a seller is more accessible, but meeting Amazon’s increasing performance requirements is still a challenge.

Amazon would be better protected from significant events like pandemics if it had tens of thousands of smaller warehouses operated by sellers or other third-parties. And sellers wouldn’t be locked in to adapt to changing rules and fees continuously. The experience required to use FBA is rising, yet it has no alternatives. Without knowledge, it becomes unprofitable for a seller. But without FBA, they cannot succeed on Amazon.

Fulfillment consistency built Amazon; without it, the marketplace would have never become an integral part. But there is a limit to how many million square feet of warehousing space a single company can manage. And there is a limit to how many small businesses can fit into the ever-increasing requirements. Perhaps March 17th, when Amazon disabled shipments for most products to FBA, was a wakeup call for just how much Amazon depends on it all running correctly. And how all of its actions trickle down to millions of sellers to adapt to. Or, like in March, for sellers to wait for things to resume to normal.