In 2022, e-commerce spending in the U.S. exceeded $1 trillion. A milestone that pre-pandemic trends predicted would only occur in 2024. Yet the industry appeared in despair marked by crashing valuations, employee layoffs, and seemingly slowing growth.

E-commerce is doing great. Much of the pessimistic sentiment surrounding it stems from looking at online spending as a share of retail sales. The dream was that the pandemic caused it to leap ahead by five or even ten years. It didn’t, and then the economy hit a wall, and the sentiment quickly hit a new low. But e-commerce spending has never been higher, there has never been easy to start selling online, and shoppers have never had more choices.

However, “e-commerce” is an obsolete term. The “e” in e-commerce stands for electronic, as the term predates the internet by decades. But its narrow constraints - retail transactions conducted on the internet - are no longer fit for modern commerce. For example, often buying now starts online but ends in physical stores: $6 out of every $10 spent shopping is either done online or influenced by online discovery. Even if the transaction didn’t happen online, the internet likely influenced it. Over the next five years, it will rise to $7 out of $10 because so much of what people buy starts on Instagram, TikTok, or Netflix.

Every television is a color television. Mobile internet is just internet. Every modern brand is a DTC brand. And so, e-commerce is just commerce. All of those were innovative qualities and distinguishing features but have since become table stakes. E-commerce as a standalone channel exists, but its borders are becoming murkier, and digital platforms are impacting retail in other ways than pure e-commerce. Attempts to quantify e-commerce spending ignore that it can no longer be distinctly separated.

Online shopping in the West is boring. Most of it is skeuomorphic. Skeuomorphism is the design concept of making items represented resemble their real-world counterparts. E-commerce is physical retail stores and shopping catalogs digitized for the web. Amazon looks the same as it did in the 90s, and Shopify is a solution for a problem as old as the web. Most of the internet’s niches started skeuomorphic but eventually evolved to internet-native ideas. That hasn’t happened yet to shopping.

Amazon won the skeuomorphic age of e-commerce. Amazon is a search box with a list of results for every imaginable demand, a perfect form of an infinite digital catalog. Of course, there are many cracks in Amazon’s platform, but they are yet to slow it down. Nor will it get disrupted by anything that does the same thing. For as long as shopping looks like a search box, Amazon will continue to be 40-50% of it in the U.S.

Social commerce looks to be that second step after skeuomorphic shopping. But it has made little progress. Maybe because shoppers don’t want that or because, for decades, social networks and e-commerce platforms have developed in parallel. Users have learned to discover products on social networks, and they play a crucial role as advertising networks, but the leap to social commerce feels forced. An argument that it will happen because it happened in China is unconvincing.

Innovation in e-commerce is happening behind the scenes instead. The incremental changes advancing the field are improved tools, more accurate data, faster shipping, reverse logistics, global payments, and more. The new-old craze is turning retailers’ websites into advertising platforms. A new breed of marketplace startups are enabling reverse commerce and B2B commerce, a market significantly larger than consumer retail. Finally, the fantasy of instant grocery delivery is not over. Yet it’s still more interesting to look at what Shein and now Temu is doing.

Contents

- Introduction

- Resetting E-Commerce Expectations

- Amazon Aggregators

- Amazon SaaS Ecosystem

- Amazon Advertising

- Buy With Prime

- Amazon Private Label Brands

- Fulfillment by Amazon

- Chinese Sellers

- Marketplaces

- Shopify's Almost-Marketplace

- Direct from China

- Social Commerce

Resetting E-Commerce Expectations

The e-commerce industry went from euphoria to despair in less than two years. Everyone had a hope two years ago that e-commerce have had a multi-year step-change when, in a few months, e-commerce penetration grew by what should have taken years (the yearly charts in 2020 showed it increasing as much as in the previous ten years in a few weeks). The assumption was that it would continue to grow from that elevated point. But as results from future quarters came, it was soon clear it was falling back to the trendline.

And yet, by Q3 2022, e-commerce spending in the U.S. exceeded $1 trillion over the trailing twelve months. A milestone that pre-pandemic trends predicted would only occur in 2024. E-commerce spending was 25% bigger than pre-pandemic forecasts would have suggested. If the pandemic didn’t happen and e-commerce grew at the rate it was growing for years before, 14-15%, the annualized run rate would have been only $815 billion in Q3. But for the first time since 2009, e-commerce growth will likely be down to single digits in 2022. The trailing twelve months were up only 9% from the period before. Admittedly, that’s compared to the historic growth in 2020 and 2021.

Total retail spending had increased even faster than online retail, however. It reached a $7 trillion run rate in Q3. Thus, despite e-commerce continuing to trend above the trendline, e-commerce penetration was falling back to the pre-pandemic trend. In Q3, 14.8% of consumer spending happened online. Excluding retail categories that don’t typically compete with e-commerce - restaurants, car dealers, and gas stations - e-commerce represented 21% of retail.

Confusingly, e-commerce had both returned and not returned to prior trends. E-commerce spending was bigger than the trendline in dollars but roughly in line with the pre-pandemic penetration percent trendline. That is, e-commerce spending was $1 trillion rather than $815 billion, but that’s only 14.8% of retail, nearly the same as the 14.2% prediction.

Misreading e-commerce growth figures over the past two years caused companies to over-stock, over-invest, over-hire, and over-build. All of that was forced to be undone in 2022, fueled by the economic headwinds. “We bet that the channel mix - the share of dollars that travel through ecommerce rather than physical retail - would permanently leap ahead by 5 or even 10 years. We couldn’t know for sure at the time, but we knew that if there was a chance that this was true, we would have to expand the company to match. It’s now clear that bet didn’t pay off,” wrote Shopify announcing layoffs in July.

Other companies shared a similar note. “At the start of Covid, the world rapidly moved online and the surge of e-commerce led to outsized revenue growth. Many people predicted this would be a permanent acceleration that would continue even after the pandemic ended. I did too, so I made the decision to significantly increase our investments. Unfortunately, this did not play out the way I expected,” wrote Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook, when announcing layoffs in November.

Shopify and Amazon were back to the trendline, having erased the “covid bump.” Across its millions of merchants, Gross Merchandise Volume (GMV) reached a $190 billion annual run rate - more than double in two years. However, had its GMV growth followed its historical performance, it probably would have gotten there either way. Amazon doesn’t report Gross Merchandise Volume (GMV); however, its quarterly results include a paid units growth metric, a measure of total units sold on Amazon. Based on that, the number of products sold on Amazon is roughly equal to levels it should have gotten to if it followed the trendline.

E-commerce spending growth is the ceiling for Amazon, Shopify, and the other major players. Consumer preferences are the ceiling for e-commerce. E-commerce in the U.S. and other countries in the West is a convenient but rarely the only solution. Thus offline retail continues to grow, and some consumers sometimes make online purchases. Every year e-commerce gets a little bigger, but it’s unlikely to play the same role as in China or India anytime soon.

Amazon Aggregators

2021 was the year of the Amazon Aggregator - firms acquiring successful brands on Amazon. By mid-2022, the sentiment surrounding the aggregator industry was heading to the “Trough of Disillusionment” stage of the Gartner hype cycle, a graphical presentation developed by a research firm Gartner to represent the maturity, adoption, and social application of specific technologies. If 2021 was the year to launch an aggregator and attract what looked like unlimited capital on a virtually copy&pasted pitch deck, 2022 was the year of survival.

It’s still unclear whether the aggregator model can work and in what form (the term “Amazon aggregator” is a misnomer since most have a unique approach). However, in the meantime, acquisitions continued - Amazon seller acquisitions declined only slightly in 2022 despite slow e-commerce growth and rising interest rates. According to conversations with investment bankers, brokers, and aggregators, the number of acquisitions in 2022 was smaller than in 2021 by 10-20%.

Many of those acquisitions were at valuations lower than in 2021. Businesses valued at upfront multiples 6x and above (excluding inventory) in 2021 were trading at 4-5x by the end of 2022. Yet those previously valued at 4-5x were relatively unchanged, selling at 3.5-4.5x. However, businesses in the 2-3x range in 2021 this year mainly attracted buyers focused on distressed assets. After the range of multiples widening for most of 2021, it narrowed this year. Amazon sellers typically get acquired for multiples of the Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE), which is a sort of an Adjusted EBDITA or annual net profit in rough terms, including add-backs of certain expenses. A business with $1 million in revenue and $250,000 in SDE profit would typically receive offers of more than $1 million guaranteed payment (4x the SDE) plus inventory and earn-out payments.

The buying process took longer because buyers were more selective and careful. Also, their due diligence methods got more sophisticated. However, sometimes performance earn-outs were not paid because the aggregator failed to grow the business they bought. Some sellers tried to help the buyer post-acquisition to meet the anticipated performance, monitoring their inventory management and advertising activity.

New funding for Amazon aggregators was down nearly 80% in 2022. After attracting $12.3 billion in 2021, only $2.7 billion was raised this year. And only 14 new aggregators announced funding rounds, compared to nearly 40 in 2021. Most of the capital - roughly 75% - came in the form of debt to be used directly for acquisitions. Most of that money is yet to be deployed. However, some of it is inaccessible due to debt covenants (debt covenants are also responsible for the multiples’ ceiling).

Despite some Amazon aggregators pausing buying, such as Thrasio and Perch, who likely made few or no acquisitions in 2022, other aggregates increased their pipeline, and more buyers joined the market. Many more buyers were aggregating but didn’t call themselves “aggregators,” and some didn’t have the same debt constraints as aggregators. These include strategic players, like holding companies of online brands and category-focused companies, and private equity funds that invest in online native brands, including brands originated on Amazon. Aggregator consolidation is yet to happen, even if some aggregators are financially unhealthy. Nevertheless, certain aggregators were actively seeking to be acquired, while others were looking to buy smaller aggregators.

Amazon SaaS Ecosystem

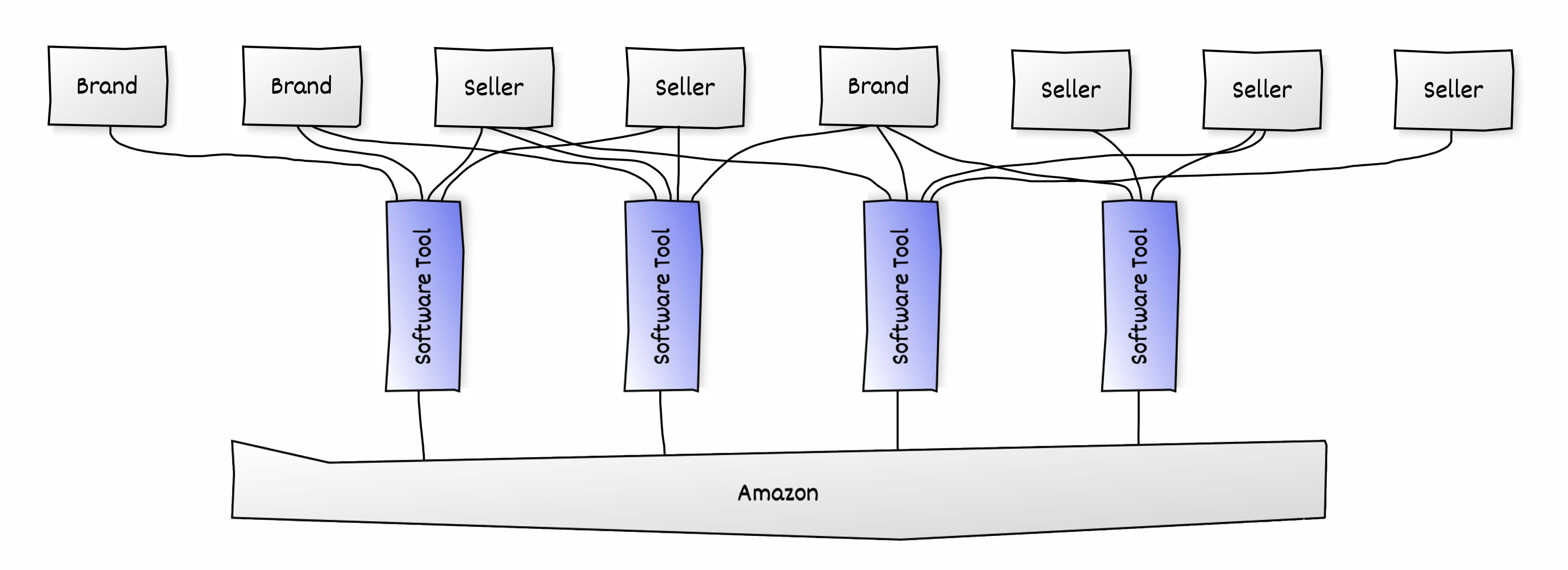

Thousands of software companies help businesses sell on Amazon with inventory management, product research, pricing, fulfillment, advertising, accounting, taxes, and more. While Amazon’s own Seller Central acts as a starting place, sellers typically use other tools to augment or replace Seller Central’s functionality. Brands that sell wholesale to Amazon also use some of those tools and a separate set of enterprise tools. However, the startups in the Amazon ecosystem (or the marketplaces niche more broadly, including eBay and others) have received little attention from investors. There have been only a handful of companies that raised equity capital. The rest - often spun out by experienced sellers - bootstrapped using their cashflows. In part, that’s because Amazon’s API creates a rigid boundary box that restricts how creative those companies can be. But also because of perceived platform-dependence risk.

That has changed over the past two years. Funding for Amazon tools has accelerated, and M&A activity has become more common. The previously capital-deprived industry is catching up to the rest of the software-as-a-service (SaaS) market. Amazon seller aggregators raising billions of dollars and some achieving valuations exceeding $1 billion are one of the drivers for the increased interest. Aggregators brought attention to the ecosystem, which meant investors started looking for other types of companies to fund. The software companies operating in this space were previously in a blind spot.

Amazon advertising has been the most active category. It’s the fastest-growing part of the Amazon ecosystem and has seen more product releases and API changes than the rest combined. Most of the leading Amazon advertising software companies have either been acquired or have raised capital. There are now also Amazon tool aggregators. Companies like Carbon6, Threecolts, and Assembly are acquiring and operating a portfolio of tools, combining them into revenue bundles. Their bet is becoming big by combining many smaller parts. Assembly was first to market by buying Helium 10, a product research tool, in 2019, and by September 2021, it had a valuation north of $1 billion.

Shopify’s ecosystem has half a dozen unicorns, including Deliverr, Attentive, ShipBob, Klaviyo, Yotpo, and Recharge. Not including aggregators and other non-software companies, Amazon has zero. Pattern surpassed a $2 billion valuation in October 2021, and Anker went public in August 2020 and now has a market cap well north of $1 billion. But neither is a software company. The closest match is CommerceIQ which raised its latest round in March 2022, which boosted the company’s valuation to over $1 billion.

Amazon Advertising

Amazon advertising prices, on average, were stable in 2022 and slightly cheaper compared to 2021. The average cost-per-click (CPC) in the U.S. was $1.06 in November, down from $1.24 a year ago. The average advertising cost of sale (ACoS) was 22%, which rises and falls with CPC changes (ACoS is the total ad spend divided by the total ad sales). The average conversion rate - the percentage of clicks an ad converts into sales - remained relatively stable at 14%. Thus the average Cost of Sale was $7-$8, down from $9-$10 in 2021 but up from $6-$7 in 2020. It took seven clicks at an average price of $1.06 to generate one sale.

Amazon’s advertising business had reached a nearly $40 billion annual run rate, growing ten times in five years by the end of 2022. Invisible in Amazon’s advertising revenue is the changing and expanding reach of its advertising. What started as a basic functionality to promote products in search results has become more elaborate every year - both on and off Amazon. Amazon advertising now includes dozens of ad types, technologies, data, and solutions for brands to reach consumers. It is now increasingly powering non-retail advertising too.

Amazon advertising is growing without ad prices increasing and not because Amazon is stuffing more ads in more places on Amazon. Amazon advertising’s growth is due to the whole network reaching further, especially off Amazon, and in more ways than bottom-of-the-funnel ads. For example, this year, it announced the ability for brands that don’t sell on Amazon, like restaurants or hotels, to advertise on its live-streaming platform Twitch, which sits on the same advertising network.

Amazon’s ad business outpaced Google’s and Facebook’s growth every quarter for the past three years. It’s still smaller, but Amazon is not competing with retailers for advertising dollars - it is going after Google and Facebook. Amazon’s ad business grew 25% in Q3 2022 to $9.5 billion. By contrast, Google’s advertising revenue, including all Google properties and YouTube, rose just 2.5% to reach $54.4 billion. Facebook’s advertising, including Instagram, shrunk for the second consecutive quarter, down -3.7% year-over-year at $27.2 billion. While Google and Facebook are significantly larger, Amazon might eventually catch up. In the third quarter of 2019, Facebook’s advertising business was more than six times bigger than Amazon’s. Three years later, Facebook is only slightly less than three times bigger. However, when Facebook’s advertising business was the size of Amazon’s, it grew as fast as Amazon is expanding today.

In the third quarter, Amazon’s advertising also grew faster than social networking platforms like Pinterest, Snapchat, and Twitter (which didn’t report Q3 results because it is no longer a public company). Combined, those three are dwarfed by advertising dollars spent on Amazon, but historically they have been growing faster. The only other recent quarter when Amazon outgrew them was the atypical second quarter of 2020. TikTok is missing from the comparison because it’s not a public company yet; thus, its financials are unavailable. TikTok’s advertising network is likely larger than Twitter, Pinterest, and Snapchat. It is undoubtedly growing the fastest among social networks.

Buy With Prime

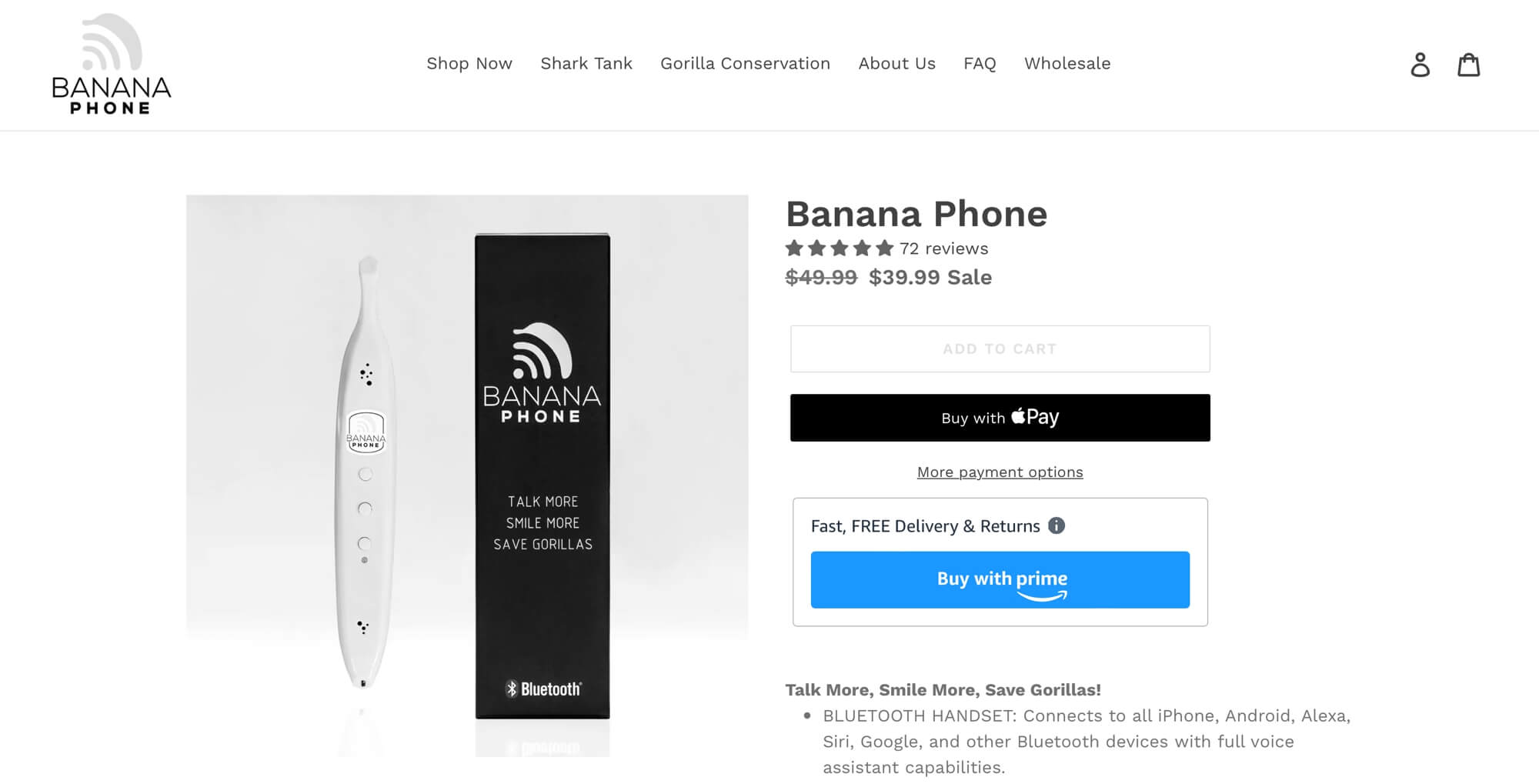

In April, Amazon introduced Buy with Prime. The service allows shoppers with a Prime membership to shop on e-commerce websites other than Amazon and check out using their Amazon account. Crucially, Amazon also handles fulfillment. For nearly fifteen years, Amazon has had services that allow shoppers to shop more easily on other retailers’ websites. First, as Checkout by Amazon, which later transitioned to Amazon Pay. Both had the same functionality as the new Buy with Prime - log in with an Amazon username, pay with a credit card and use a shipping address stored in the account.

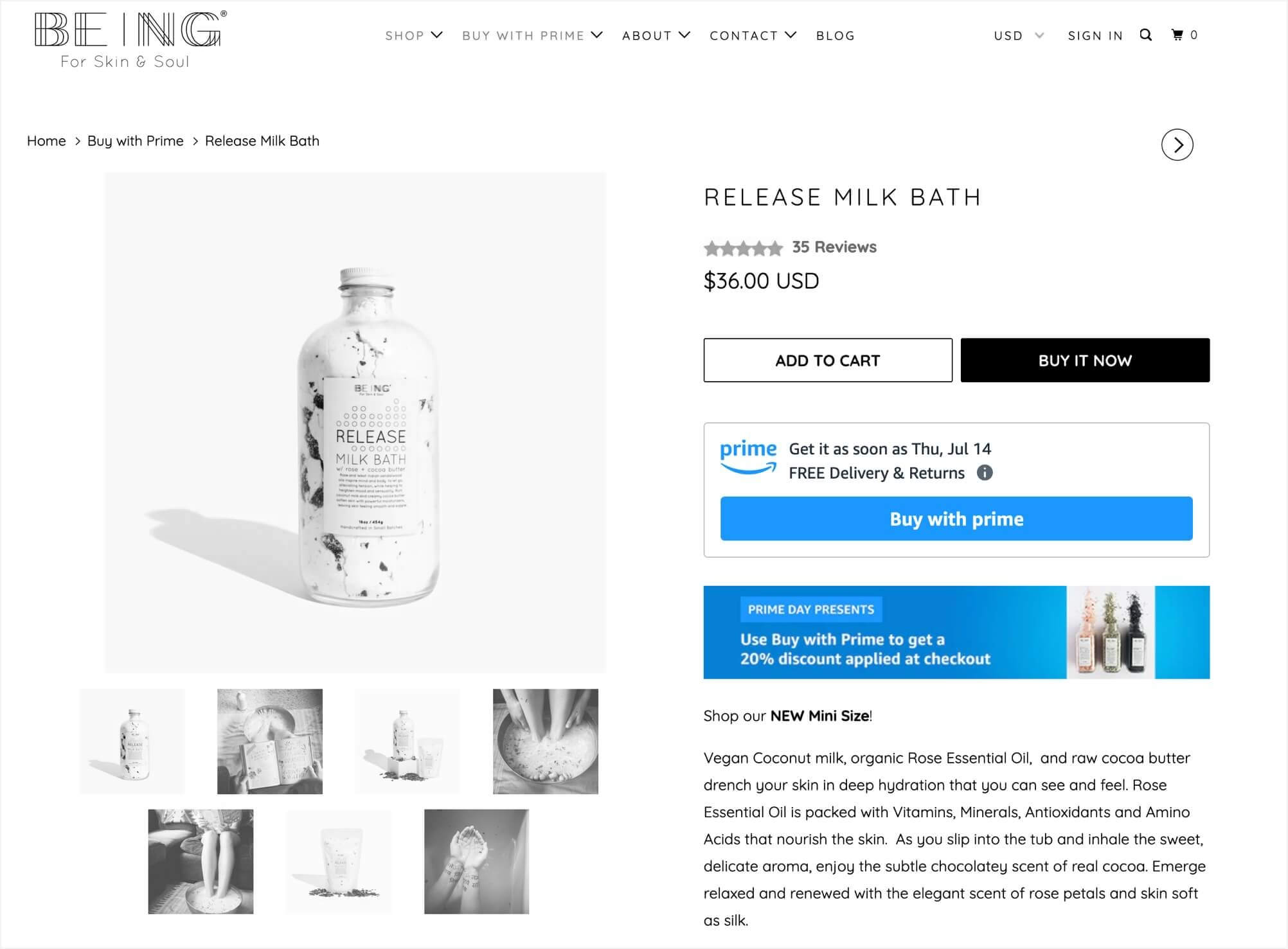

Buy with Prime merged Amazon Pay with Amazon Fulfillment. Rather than only handling payments - a convenience feature competing with Apple Pay and others - it also guarantees delivery time and free shipping. It achieves that by requiring sellers to send their merchandise to Amazon warehouses first. Buy with Prime only works with inventory stored at Amazon warehouses. Thus, the service has been adopted mainly by brands that already sell on Amazon or by Amazon sellers looking to launch a DTC website.

When shoppers click the “Buy with Prime” button on a brand’s website, they get prompted to sign in to their Amazon account. They can then complete the order using their preferred payment method stored in their Amazon account. However, shoppers cannot see or track Buy with Prime orders on the Amazon.com orders page or in the Amazon mobile app. The Prime member’s data shared with the merchant includes their name, email, shipping address, phone number, and the last four digits of their payment method used during checkout. Merchants can use that data to build direct relationships with customers. However, they are not allowed to share it with “any third party that identifies shoppers as Prime members unless it is solely for providing a service to the merchant.”

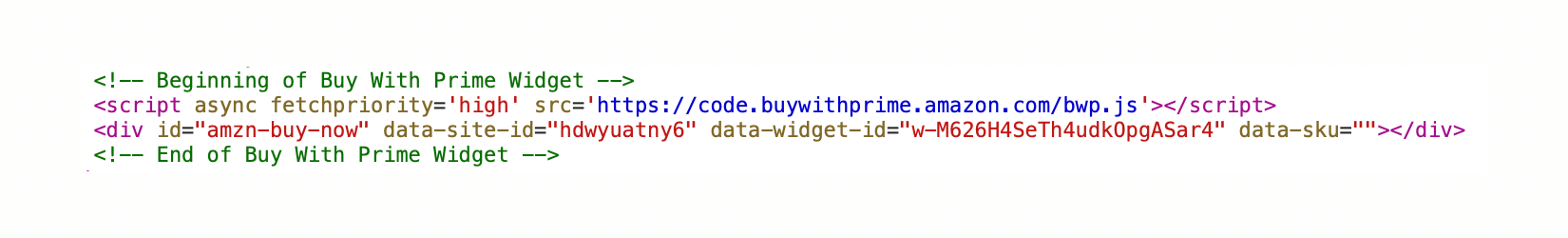

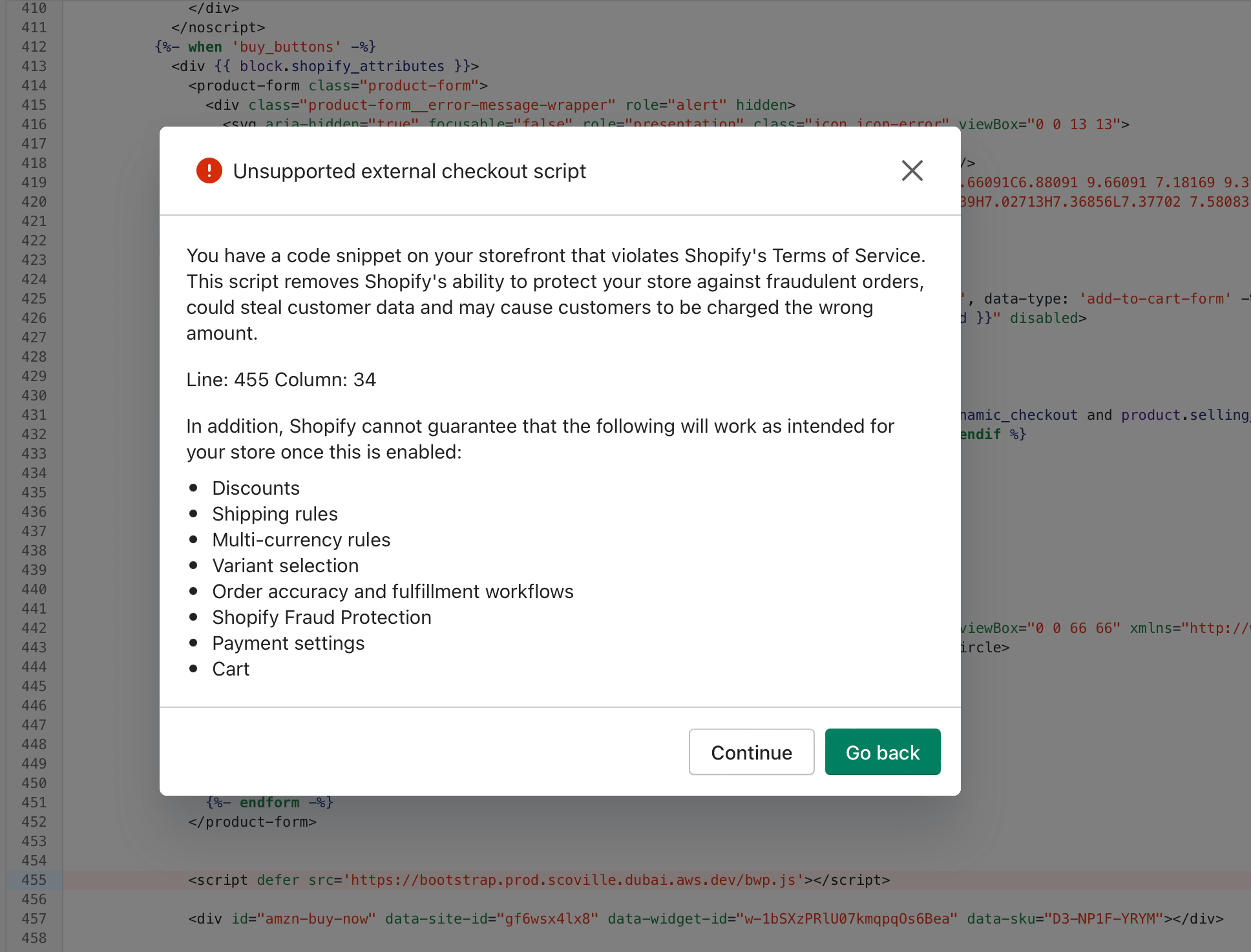

Once merchants have signed up for Buy with Prime, Amazon generates an HTML button code that they need to add to the product template. There are no extensions or plugins to automate this for any e-commerce platform, including Shopify or BigCommerce. Thus the integration is basic and is limited to the few lines of button code Amazon provides. The method Amazon used to implement Buy with Prime allowed it to support all platforms on day one and, perhaps crucially, not have to ask for permission from them.

In September, Shopify started to block the Buy With Prime code. It started warning merchants trying to save the edited template that the code included an “Unsupported external checkout script.” Merchants could still proceed but had to acknowledge that they understood Shopify would not be responsible. “You have a code snippet on your storefront that violates Shopify’s Terms of Service. This script removes Shopify’s ability to protect your store against fraudulent orders, could steal customer data and may cause customers to be charged the wrong amount,” read the message to merchants. Amazon later slightly adjusted the integration code, and Shopify no longer warned merchants trying to use it.

Buy With Prime ambitions span beyond one-click checkout. Towards the end of the year, Amazon announced that brands could create a Buy with Prime page within their storefront on Amazon and drive traffic to it using Sponsored Brands advertising. From this new page, shoppers could open the brand’s website and purchase the product using Buy with Prime. “We think that giving DTC merchants the ability to reach purchase-ready Amazon shoppers as they search for products will be a big win for: 1) Shoppers, who can find new products on Amazon and buy them direct from their favorite brands, with the promise of free, fast Prime delivery and the A-to-Z guarantee, and 2) DTC Merchants, who will have a new avenue they can use to grow their brands and increase their DTC ecommerce sales,” wrote Dave Lefkow, Principal Product Manager at Amazon, on LinkedIn.

For the first time, Prime Day deals were available beyond Amazon this year. A few dozen stores had a “Use Buy with Prime to get a 20% discount applied at checkout” or similar banner. Amazon even created a page listing the participating stores on its website at www.amazon.com/buywithprime. As more brands adopt Buy With Prime, Amazon will likely add more features to its app to discover them. Over time, Amazon could become a marketplace for DTC brands.

Amazon Private Label Brands

In July, The Wall Street Journal suggested that Amazon was killing off its private-label brands. “Amazon has started drastically reducing the number of items it sells under its own brands,” wrote Dana Mattioli for The Wall Street Journal. “Over the past six months, Amazon leadership instructed its private-label team to slash the list of items and not to reorder many of them, the people said.”

However, Amazon is staying in the private label business. While it slashed some slow-moving items, all of Amazon Basics and its other private label brands’ best-sellers are still available. By the end of the year, Amazon still had the same number of best-sellers as it did for the past two years. Amazon Basics had 1,338 best-sellers, nearly as many in 2021 and 2020. A best-seller product is one to have made it into the top 100 in any category or sub-category on Amazon. The number of best-sellers has remained flat for over two years. That indicates Amazon didn’t get more aggressive to overtake more niches. Many of the slashed unsuccessful products were perhaps intended to become best-sellers but, for various reasons, failed to stick.

Amazon has considered exiting the private label business to appease regulators, but it is yet to happen. “Top Amazon leaders have also internally discussed making a more drastic move to ward off regulators: abandoning its private-label business altogether,” wrote Jason Del Rey for Vox. “At least as recently as last year, several top Amazon executives, including its current worldwide retail CEO Doug Herrington and its general counsel David Zapolsky, expressed a willingness to make this different but significant change if it meant avoiding potentially harsh remedies resulting from government investigations in the U.S. or abroad, according to a source with knowledge of the discussions.”

While Amazon’s private label brands span tens of thousands of products, most of its sales come from a few dozen top products. For example, the infamous Amazon Basics batteries. Amazon hasn’t stopped selling those, nor did it any other best-sellers. Thus the impact of trimming some slow-moving products from the long tail is tiny. And in no way does that indicate Amazon is abandoning the private label business. Not until Amazon stops selling the batteries.

Across its top brands like Amazon Basics, Amazon Essentials, Simple Joys by Carter’s, Amazon Commercial, Amazon Basic Care, Goodthreads, Amazon Elements, Pinzon, and others, all of the best-sellers were still there. Amazon only trimmed failed products from its portfolio. Yet that’s inconsequential since they were not contributing meaningful sales. “Under Mr. Clark, private-label teams did a profitability review of each private-label item, determining which ones didn’t sell enough to hit their profit threshold and targeting them to be phased out,” wrote Dana Mattioli. This practice is typical for retailers.

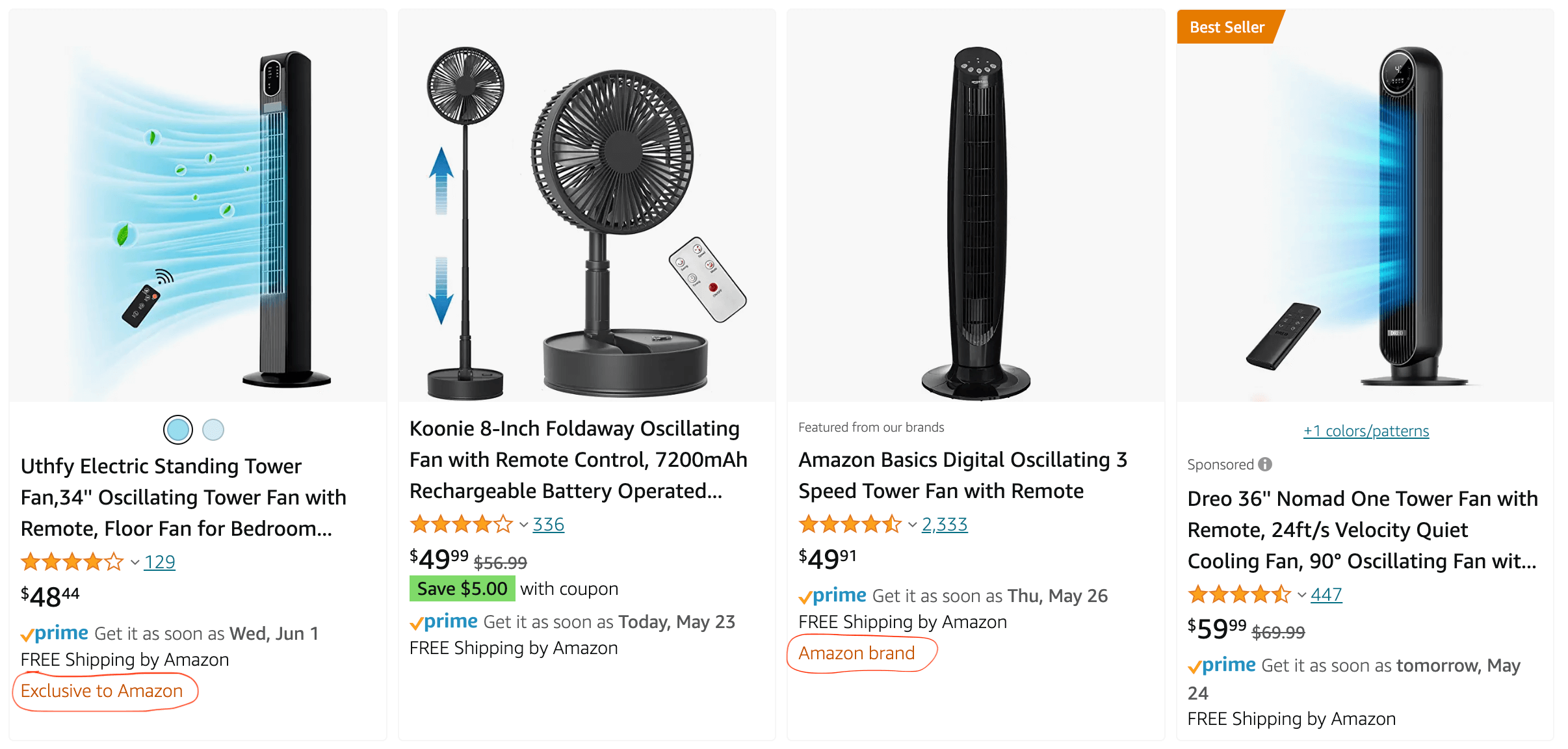

Even before the noise of the potential abandonment of Amazon Basics, in March, Amazon started identifying its brands in search results, tagging them with an “Amazon brand” or “Exclusive to Amazon” badge. Previously, it was inconsistent in disclosing which products it owned: Amazon Basics and Amazon Essentials are unmistakable as brands owned by Amazon, but the portfolio includes many more brands without an obvious connection to the company.

It’s unclear why Amazon increased transparency - no other retailer has similar badging online. No regulation passed requiring it, and it is only a feature in the U.S., despite Amazon also selling private label products in other markets. The new badge is likely a preemptive response to continuing antitrust inquiries. Some of which have centered around its private label efforts. Attempts to analyze Amazon’s brands in the past first involved a complicated effort to identify the list of brands.

Fulfillment by Amazon

Amazon has tied selling on Amazon to its fulfillment service, Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA). But it now chaotically restricts how much space it allocates to sellers while at the same time raising fees. In October and November, many sellers reported that Amazon significantly reduced their FBA storage limit. With the space restricted, they were unable to send in inventory. Without inventory in FBA, they lost sales they could have had. They could not use 3PL warehouses since Amazon ranks FBA sellers higher.

On the surface, FBA looks like a virtually infinite fulfillment network, promising to scale with the seller. Not unlike Amazon’s cloud hosting service AWS. But sellers cannot always pay for more FBA capacity when they want it. Amazon alone decides how much they can get. FBA changed from service sellers can rely on to a service they hope Amazon will allow them to use. A big source of frustration for sellers was the sporadic and seemingly random changes to storage limits followed by poor communication. There have been multiple restrictions like that over the past two years. But the biggest problem was the artificial ceiling on the seller’s revenue.

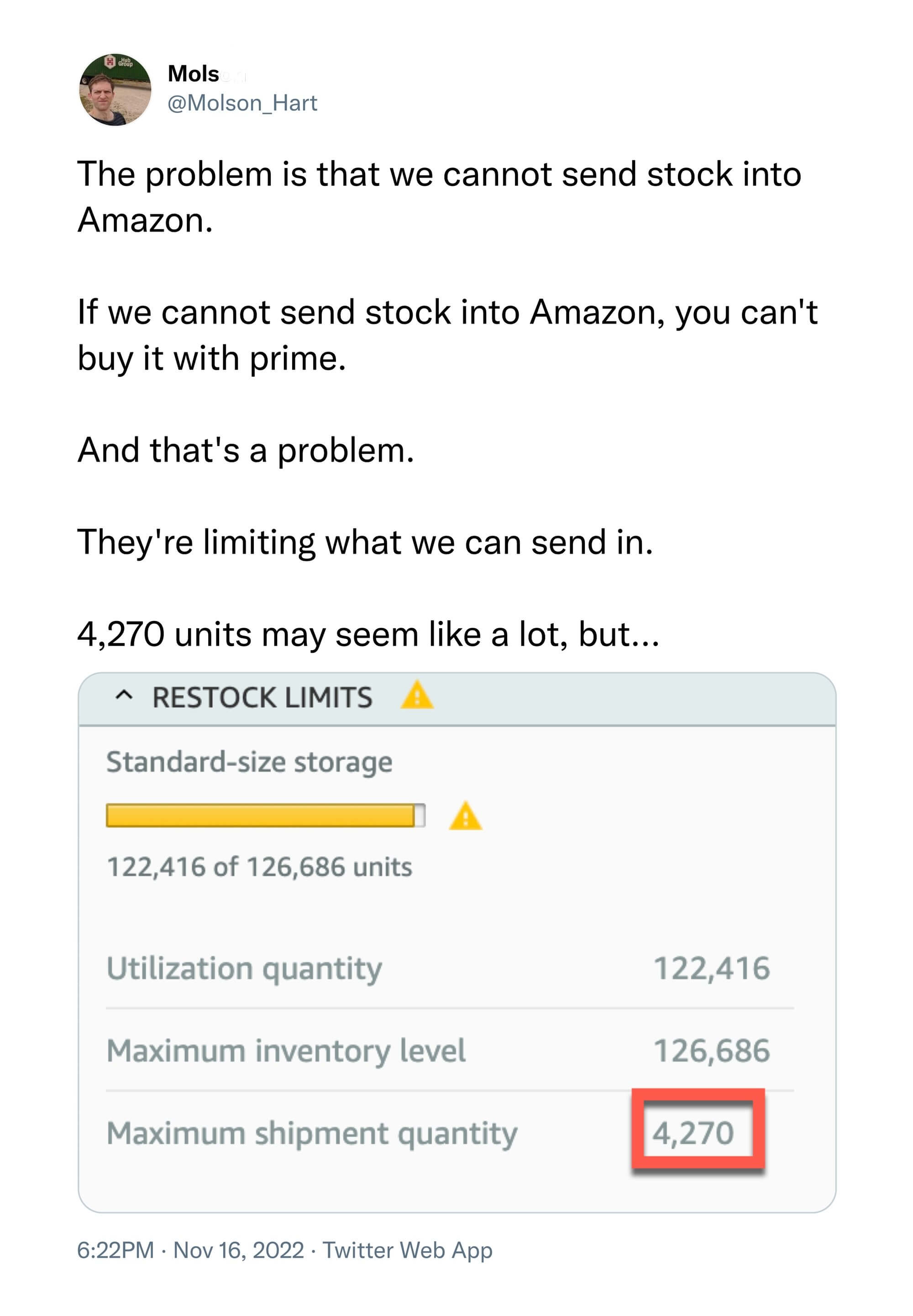

“My company paid Amazon ~$4 million dollars in the last 12 months and we’ve been selling on Amazon for over a decade. I have no idea what they’re doing right now. And neither do they,” shared Molson Hart, CEO of Viahart, an educational toy seller, on Twitter. “The problem is that we cannot send stock into Amazon. If we cannot send stock into Amazon, you can’t buy it with Prime. And that’s a problem. They’re limiting what we can send in. 4,270 units may seem like a lot, but… Our forecasts, which are based on 10 years of experience in the educational toy industry, say that we’ll sell over 243,000 between now and Christmas.”

Amazon blamed overstocked sellers for the increase. “This year, we saw some sellers use more of our storage than we expected or believe was needed to serve customers well, and that constrained how much product from other sellers could be sent into FBA,” wrote Dharmesh Mehta, Vice President of Worldwide Selling Partner Services at Amazon. Overstock issues were rampant this year, but they shouldn’t have affected sellers that didn’t have them.

The fundamental issue with FBA storage limits is that Prime is tied to FBA, and Amazon is tied to Prime. That is, most shoppers on Amazon are Prime members, and thus Amazon is tuned to favor Prime selection. But offering Prime selection requires the use of FBA. In 2021, Amazon was fined nearly $1.3 billion by Italian regulators for this exact tying.

FBA is not an optional service but a required one, and thus according to Marketplace Pulse research, over 90% of top sellers on Amazon use it. Amazon sellers have no choice but to use FBA because it is nearly impossible to be competitive on Amazon without it. The few sellers that don’t use it are often in categories unfit for FBA, like books. Amazon would argue that FBA is the cheapest and best option for sellers. And it often is. But sellers still have to use it when it isn’t - and it wasn’t the cheapest and best option often over the past few years.

Amazon has increased fulfillment fees by over 30% since 2020. A series of small fee jumps has added up to a meaningful increase. Amazon is passing off its growing costs to third-party sellers. Amazon charged sellers $5.06 to ship a 1lb item during the holiday season (October 15th-January 14th); in 2023, it will charge $4.75. The fee for fulfilling the same product in 2020 was $3.48 - it has increased by nearly 40%. In 2023, smaller items will be roughly 30% more expensive to fulfill, while large and heavy items will be 20% more expensive compared to 2020. Since most Amazon sellers use FBA, these fee increases affect all and ultimately mean consumers are paying more.

The fees increased in steps. For example, Amazon first raised the fee to fulfill a 1lb item by 77 cents on June 1st, 2021. Then, on January 18th, 2022, it increased by 27 cents. In April, Amazon added a fuel and inflation surcharge of 23 cents. And finally, the fee increased by 31 more cents during the holiday season. In total, it went up by $1.27. The fees will go down after the holiday season, but not all product sizes will fall back to the pre-holiday levels.

| Year | Small 12oz | Large 1lb | Large 3lb | Small oversize |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | $2.41 | $3.19 | $5.09 | $8.13 |

| 2019 | $2.48 | $3.28 | $5.26 | $8.26 |

| 2020 | $2.63 | $3.48 | $5.42 | $8.26 |

| 2021 | $2.84 | $4.25 | $5.68 | $8.66 |

| 2022 | $3.07 | $4.52 | $5.79 | $8.94 |

| 2022 April | $3.22 | $4.75 | $6.08 | $9.39 |

| 2022 Peak | $3.43 | $5.06 | $6.60 | $10.44 |

| 2023 | $3.58 | $4.75 | $6.39 | $9.73 |

“At a certain point, you can’t keep absorbing all those costs and run a business that’s economic,” Amazon CEO Andy Jassy told CNBC in April. “We have previously absorbed these cost increases, but seasonal expenses are reaching new heights,” Amazon wrote in an update to sellers in August. USPS, FedEx, and UPS have all raised fees and introduced peak holiday surcharges over the past two years. Overall, fulfillment has gotten more expensive on and off Amazon FBA - many third-party logistics providers (3PLs) have been increasing their fees too.

Sellers, too, couldn’t keep absorbing increasing costs, and thus they raised prices. When Amazon increases fees, sellers increase prices to maintain a profit margin, and when it reduces available FBA storage, they watch products sell out and miss out on sales they could have made. Furthermore, since Amazon penalizes sellers for offering their products cheaper on other channels, sellers inevitably raise prices across all marketplaces.

Chinese Sellers

For the first half of the year, it looked like Chinese sellers were quitting Amazon. Domestic sellers were regaining market share on Amazon, reversing the multi-year trend of losing to predominantly Chinese sellers. “Amazon helped these [Chinese] exporters reach a huge and lucrative audience; now, they have an urgent need to wean themselves off,” wrote Rui Ma in Rest of World.

“In the future, Chinese foreign trade enterprises should avoid reliance on Amazon,” wrote Hong Yong, Ministry of Commerce-linked Associate Research Fellow, in April. Hong Yong published an op-ed in the overseas edition of the People’s Daily titled “Defusing the Risk of “Chokehold” in China’s Cross-border E-commerce Channels.” People’s Daily is the largest newspaper in China; it provides direct information on the policies and viewpoints of the CCP.

The article listed high and increasing fees (because of advertising), shutting down and freezing of funds of hundreds of seller accounts, and lack of access to customer data as reasons for diversification from Amazon. The sentiment got louder when Amazon’s seller suspensions in 2021 sent shockwaves through China’s e-commerce industry. (Those sellers got suspended for paying for fake reviews and other violations, which plenty in China continue to view as unjustified)

However, by the end of 2022, Chinese sellers recouped the market share they lost on Amazon. Chinese sellers’ market share of the top sellers decreased to 40% in February, but by December, it was back up to 45%. Thus, while various headwinds affected their performance, and many wanted to reduce their reliance on Amazon, no other marketplace could offer the same reach.

Since Walmart opened its marketplace to international sellers in March 2021, it has added more than 25,000 sellers from China. By the end of this year, they represented roughly 40% of new sellers every month. Walmart’s marketplace is possibly the most popular channel to diversify beyond Amazon. Walmart has also invited sellers in India and Canada to join by hosting events there in 2022, but so far, they have only added hundreds of sellers. It is unlikely they will reach Chinese sellers’ numbers, but more will join.

Marketplaces

Amazon added one new country in 2022 - Belgium. It launched there in October. The marketplace was Amazon’s tenth active marketplace in Europe and brought the total number of countries to 21. Like its other launches in Europe, practically all sellers present at the Belgium launch are existing sellers from other Amazon’s European marketplaces - mainly businesses from China, Germany, the U.K., Italy, France, and Spain, rather than Belgium.

Amazon will next launch in Colombia, South Africa, Nigeria, and Chile. According to Amazon documents obtained by Eugene Kim of Insider, all will launch in spring 2023. After those countries go live, Amazon will be a retailer in 25 of the 50 largest economies.

Amazon.com in the U.S. remained the most important market, representing 45% of total visits across its 21 worldwide marketplaces. The next three - Japan, Germany, and the U.K. - commanded roughly 10% each. The top five markets (U.S., Japan, Germany, U.K., and India) represented nearly 77% of web traffic. However, mobile likely represents 50% or more of orders on Amazon; thus, web traffic is no longer the only key indicator. But it still showcases that Amazon’s expansion in new, increasingly smaller countries will take years to contribute to its business materially.

35% of the active sellers on the Walmart marketplace joined it in 2022. This year, it overhauled the registration process from requiring sellers to apply by filling out a questionnaire to allowing them to create a seller account immediately and fill out additional details later. As a result, more than twice as many sellers were becoming active each month. Many of them were using Walmart Fulfillment Services (WFS), not unlike most Amazon sellers that use its equivalent FBA, because it has become virtually a prerequisite to rank well in search results.

Target’s marketplace remained invite-only. It only had less than 600 sellers by the end of the year, nearly four years since it first opened to sellers. “It will remain invite-only as we think through who are the right trusted partners that we are looking to actually complement our assortment with,” said Cara Sylvester, Chief Marketing and Digital Officer at Target, when discussing fourth-quarter results last year. There haven’t been updates from the company since, nor changes to how quickly it is adding new sellers (not because of a lack of interest from sellers).

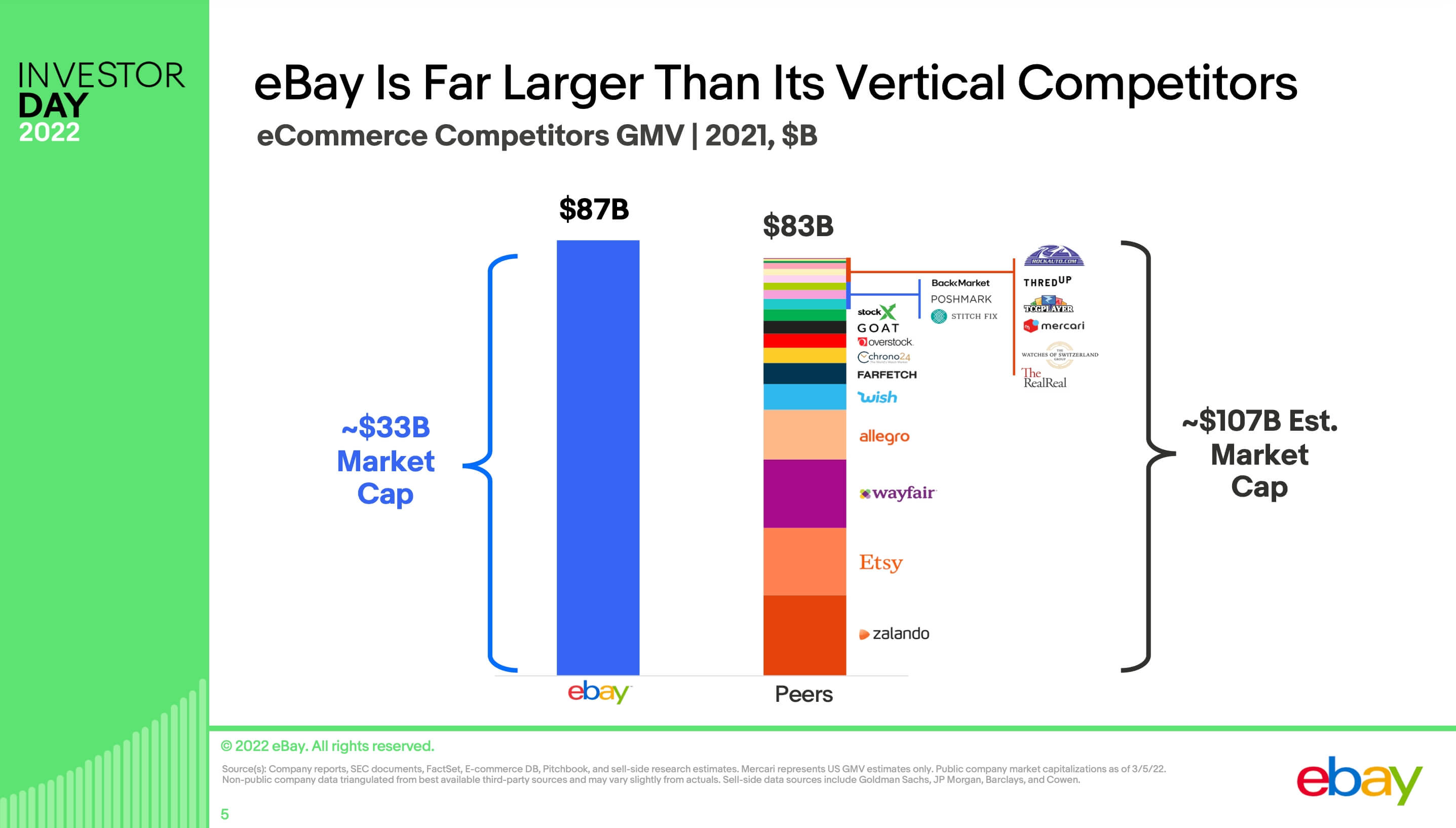

eBay conceded it lost to Amazon. “When you’re talking to business-to-consumer sellers who are primarily selling ‘new and in-season’, they’re going to be more likely to sell on Amazon or Walmart,” said Jamie Iannone, CEO of eBay. “Ebay was trying to move into that space. I don’t think it’s a long-term place where we can win,” he added.

eBay had refocused on select categories it calls “focus categories,” and high-spending users nicknamed “enthusiast buyers.” Focus categories include jewelry, sneakers, handbags, and collectibles like trading cards. Enthusiast buyers - roughly 12% of active buyers - shop on eBay multiple times a year and spend more than the average user. The refocused eBay is searching for a bottom - according to eBay’s guidance, eBay’s global GMV in 2022 will reach $72.7 - $74.7 billion. That’s nearly identical to the $72.1 billion GMV in 2019.

Hundreds of companies took a category on eBay and improved selection, experience, or business model - focusing on categories and enthusiast buyers years before eBay did. Combined, they are larger than eBay and have valuations exceeding eBay’s multiple times. During eBay Investor Day 2022 event, Steve Priest, Chief Financial Officer at eBay, shared a slide that eBay’s vertical competitors like StockX, Etsy, Wish, Farfetch, and fifteen more combined, are smaller than eBay in GMV but valued more than three times more. eBay intended to remind how big it still is even compared to competitors combined. But it showed how many companies took parts of it and made them better instead.

Shopify’s Almost-Marketplace

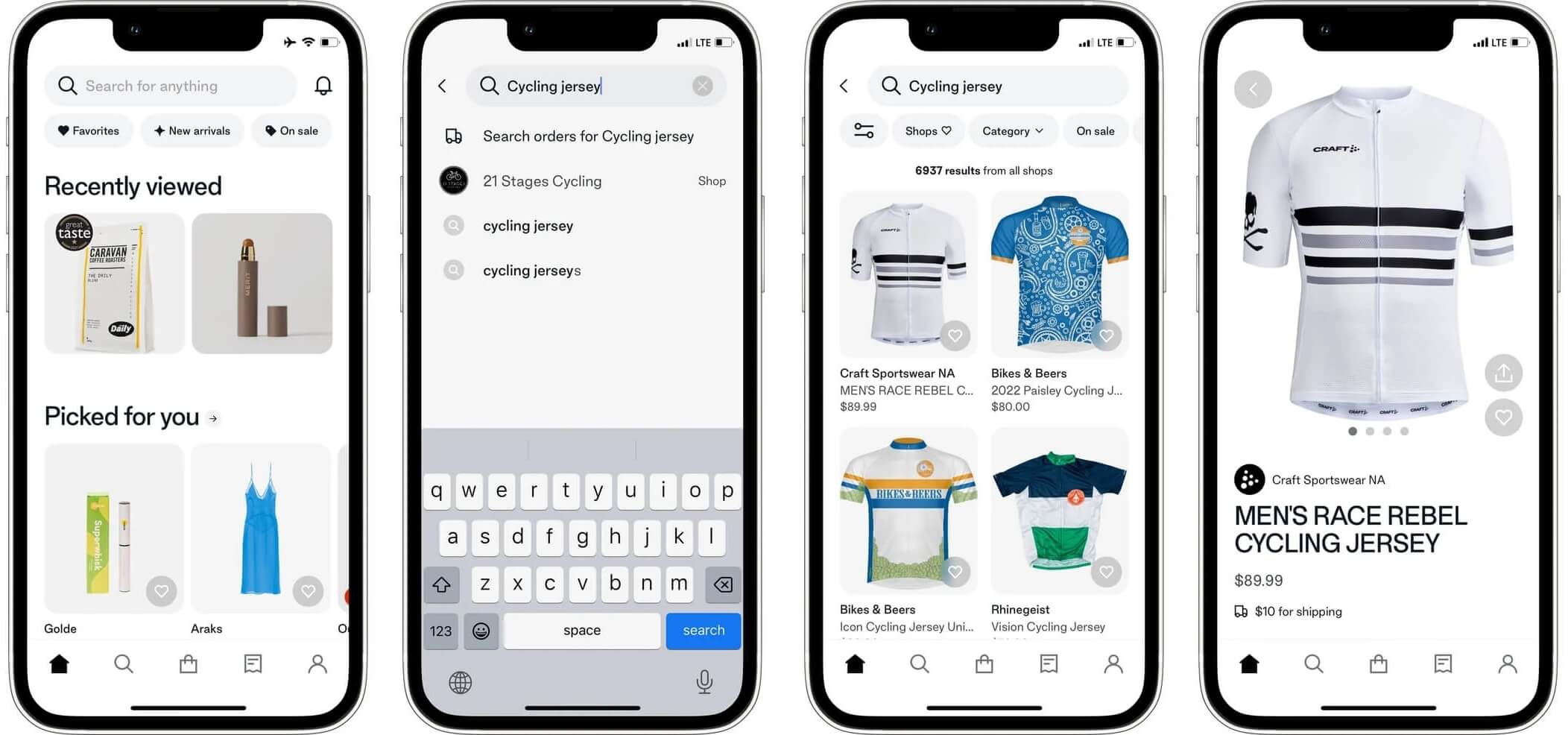

Shopify remained undecided about whether it wanted to operate a marketplace. Shopify’s Shop app added a “Search for anything” search box, but only as a test visible to some users. It allows customers to search for items they previously purchased, merchants matching the search term, and products sold by any of Shopify’s merchants. For example, a “cycling jersey” search returned 6,937 results.

In an interview with Harley Finkelstein, president of Shopify, in May 2021, Niel Patel of The Verge asked, “Do you see yourself headed in that more consumer direction, where you run basically a catalog for lots of independent businesses?” Harley answered, “No. We have no plans to be a marketplace.” But to a limited set of users that have the universal search visible, Shopify is a marketplace. Shopify hosts many brands that are often unavailable on other channels. However, there is no simple way to discover them. Unless customers see advertisements on Facebook or Instagram, they won’t know about the different shopping options. “Search for anything” solves that.

The search functionality completes Shop app as a fully-fledged marketplace. It had the other parts - adding their items to a shopping cart and checking out without leaving the app - for over a year. Adding search allows the entire shopping journey to happen in-app. The only missing feature is a universal shopping cart since, despite being able to add items from multiple stores to the cart, they cannot be checked out at once.

A universal search means a ranking algorithm and deciding what metrics influence higher ranking. Eventually, universal search also means an advertising platform for merchants who want to pay to rank higher. Those are likely some of the reasons why Shopify has been reluctant to go all-in.

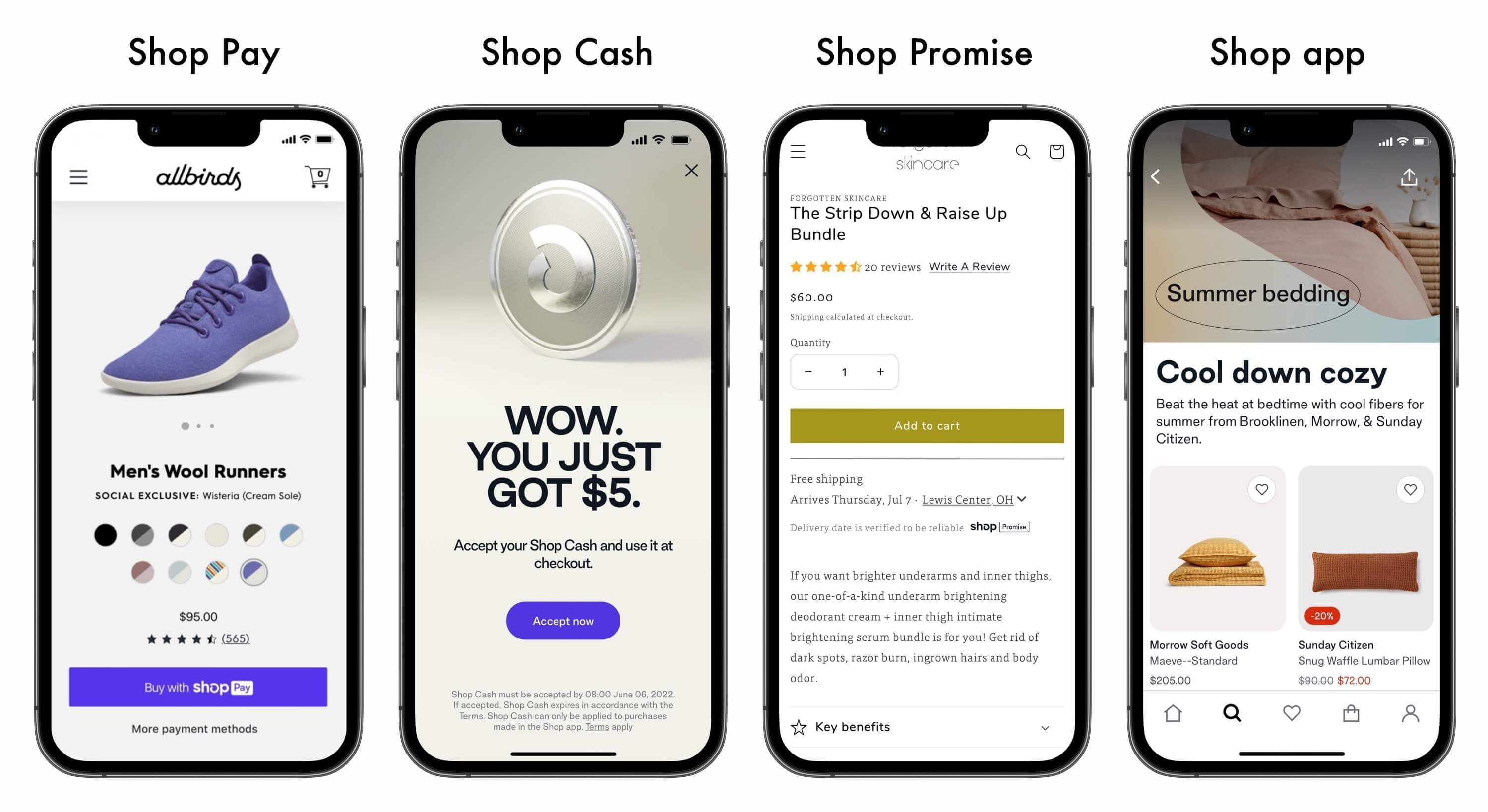

There is also a question of whether Shopify should become a consumer-facing brand, but it has already been going that route with the Shop app, Shop Pay, Shop Promise, Shop Cash, and more. Shop Pay, a payment gateway and one-click checkout, has existed for a few years. This year, Shopify launched a 1% cashback Shop Cash for purchases made via Shop Pay. Consumers could only spend Shop Cash in the Shop app. Shopify also introduced Shop Promise, a badge that signals two-day delivery and hassle-free returns. Shopify can promise that because those items are stored in its fulfillment network.

Today, brands decide which e-commerce software to use based on features, price, and preference. If the Shopify consumer-facing ecosystem becomes successful, that will pull more brands to join despite other considerations - competing software systems are invisible; Shopify is not. Shop Pay, Shop Cash, and the Shop app create a virtuous cycle. As more shoppers get Shop Cash cashback, they will use the Shop app to find where to spend it. More brands will want to be found there, so they will join Shopify, enable Shop Pay payments, and boost cashback. Then, even more shoppers would get cashback, accelerating the flywheel.

Shopify would be the second-largest e-commerce retailer in the U.S. if all its merchants were treated as one. This comparison was silly because consumers didn’t go shopping at Shopify - Shopify was invisible to them. However, as Shopify expands its consumer-facing ecosystem and continues universal search experiments, it could soon compete with other retailers for shoppers.

Direct from China

In May, Shein, a fast-fashion marketplace, became the most-downloaded app in the U.S., surpassing giants like TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter and far ahead of Amazon. Shein is the connector between China’s garment factories with Western Gen-Z customers. Its critical innovation was that Shein dressed the supply chain advantage in an experience that delights. Its vertical focus allowed it to provide a better experience - Shein looks and feels like a brand store rather than a random selection of products. Something AliExpress, Wish, and Amazon failed to replicate.

Shein sold $30 billion worth of clothes in 2022. It is the biggest digital-only clothing retailer. And yet the app is arguably unknown to anyone but its target audience. Shein could soon be the world’s largest fast-fashion retailer, surpassing Zara and H&M. Its ambitions are not limited to clothing, though, as it has already expanded into other categories. Nor it wants to rely on manufacturing in China exclusively, thus starting manufacturing in Turkey.

“Shein’s competitors aren’t quite these fast fashion stalwarts, or other e-commerce platforms like Amazon. Its greatest competitor is inattention. Whenever customers shopping for clothes find something that diverts their attention away from Shein’s stream of new product launches, Shein’s sales are in danger,” wrote Mark Greeven. Shein has flaws, though, too. Some of those issues include its environmental impact, sustainability record, and proliferation of counterfeits. Shein’s ultra-fast-fashion push and lowest-price focus beat the competition, but many argue that governments, regulators, and environmentalists should slow it down.

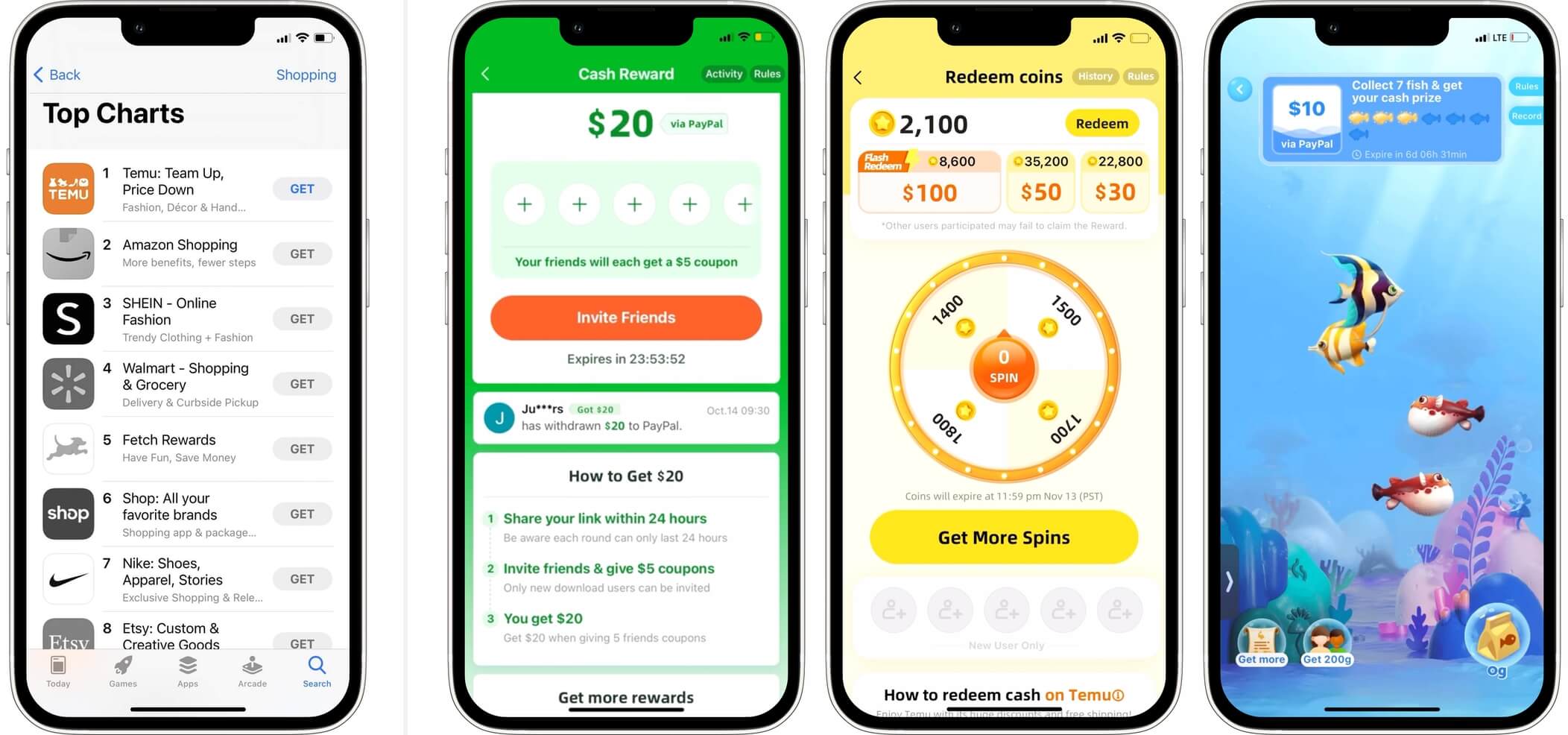

Following Shein’s footsteps, Temu became the most-downloaded shopping app in the U.S. in late October. Launched by China’s Pinduoduo in early September, it was the latest marketplace to bring China-made goods to Western consumers. By November, it was the most-downloaded app across all categories and stayed there for weeks. Temu’s quick rise to the top is driven almost exclusively by advertising and gamified referrals - asking users to invite friends to get a free product or a cash payment.

Temu competes with AliExpress and Wish - just like theirs, its value proposition is very cheap goods that ship in a week or less. For example, the most popular item in the Shoes department was the $3.99 slippers that sold more than 100,000 units. Identical products at similar prices are available on AliExpress and Wish, but the item costs more than $15.00 on Amazon.

Very few apps make it to the top of the most-downloaded apps. The list had the same incumbents - Amazon, Walmart, Target, eBay, Nike, and Etsy - for years. Temu is aggressively growing its user base, even if primarily through gamified referrals, which will churn quickly. The app’s parent company, Pinduoduo, is one of China’s e-commerce giants that has risen in prominence and market share over the past five years. Pinduoduo built its business on mobile-first, group buying, social commerce, gaming, and consumer-to-manufacturer (C2M). However, Pinduoduo didn’t bring most of those innovations to the U.S. with Temu yet.

“Why buy a $40 bikini made in America when you can buy a $4 bikini directly from China? For that matter, why buy a $20 bikini made in China but imported by a U.S. company like the Gap when you can buy a $4 bikini directly from China?” in 2018, Alana Semuels wrote for The Atlantic. Shein has been the most successful at bringing this vision and, unsurprisingly, has become the biggest digital-only clothing retailer. Temu wants to be there too. Pinduoduo famously allowed users to recruit friends and family to buy at a discount, but its greatest strength is its supply chain. Temu and Shein are both supply chain companies first and e-commerce retailers second.

Social Commerce

“Mark Zuckerberg had high expectations for turning Facebook and Instagram into shopping destinations. Now, the effort he was once intensely focused on has been boiled down to ads,” wrote Sylvia Varnham O’Regan for The Information. “Meta’s CEO had high expectations for the company’s push into online shopping. But now Meta is scaling back its commerce ambitions following internal strategy debates, slow sales and a deepening crisis over its advertising revenue.” In a different article, Sylvia wrote, “Instagram is planning to drastically scale back its shopping features, the company told Instagram staffers on Tuesday, as it shifts the focus of its e-commerce efforts to those that directly drive advertising.”

All social networks have launched social commerce functionality like in-app checkout. But none of it is social, nor did they directly generate material sales. Social apps are essential shopping discovery platforms but mainly capture dollars through advertising.

Prime Day is the best example of social commerce in the U.S. - videos tagged with #primeday2022 and related hashtags have been viewed 77 million times on TikTok. Shoppers turned to social networks to discover the best deals rather than trying to find them on Amazon. Last year, it was 30 million, and the year before - 6 million. In 2019 it was virtually zero. Not only has TikTok gotten more popular in the U.S., but its users started watching more shopping-related content. Shoppers turned to TikTok because, during Prime Day, Amazon presents an overwhelming yet infinity-long list of deals, leaving it to the shoppers to find what they like.

“I had no idea what to buy on Prime Day, so I went to TikTok,” was a sentiment shared by many shoppers during the event. “True story: when I wanted to find out about all the best Prime Day deals, the first place I searched? TikTok,” shared others. Most of Prime Day was on TikTok rather than Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter; its content model works best for that. TikTok is the best at quickly personalizing content to each user - TikTok surfaced videos based on recent engagement with other Prime Day-tagged videos. For comparison, engaging content was again missing in Amazon’s own live video stream during Prime Day. Amazon and TikTok didn’t work together to enable this, and those videos didn’t have links to products so shoppers could easily purchase.

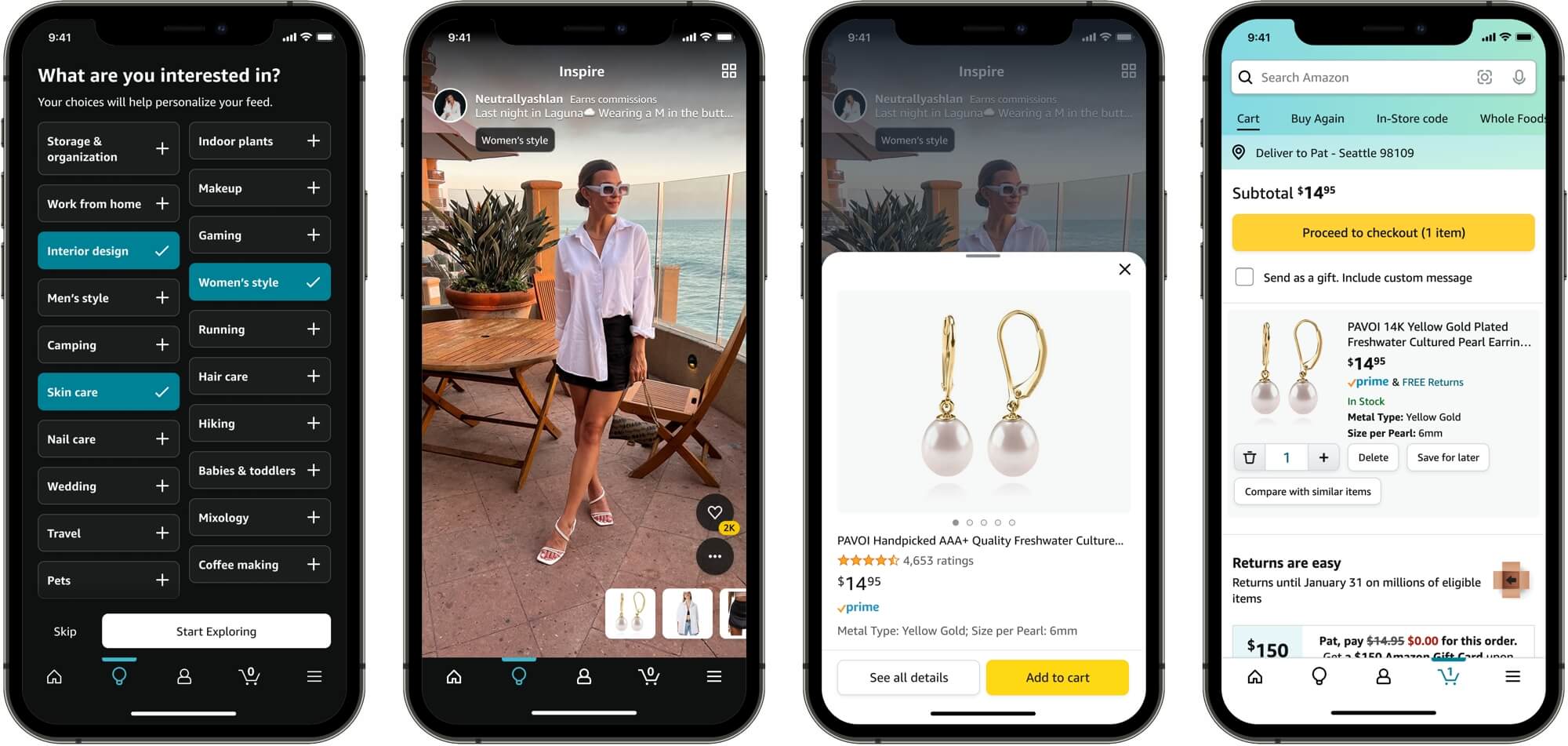

The hashtag #amazonfinds has 34 billion views on TikTok. TikTok wants some of those views to turn into in-app commerce, and Amazon wants those views to happen on Amazon. Amazon hopes to figure out social commerce before social networks can solve shopping. In December, it announced TikTok-like functionality called Inspire that could turn Amazon into a discovery destination. It is “an in-app shopping experience that gives customers a new way to discover ideas, explore products, and seamlessly shop from content created by other customers, influencers, and brands they love.” The experience is similar to a TikTok feed, featuring endless photos and videos shoppers can swipe through. Once they see something they like, they can buy it in a few clicks.

Amazon wants shoppers to spend time in the Amazon app even when they don’t want to shop. It is trying to solve a weakness most shopping websites and apps have in the U.S. - consumers only open them when they know they need something. They do not open them to browse casually (they open apps like TikTok instead). Thus e-commerce is very transactional and doesn’t have the same discovery and browsing experience as physical retail. “The internet lets you buy, but it doesn’t let you shop,” wrote independent analyst Benedict Evans.

The challenge is that Amazon’s Inspire content will compete for attention with other apps like TikTok, YouTube, Instagram, and dozens more. While those have added shopping functionality over time, they are not focused exclusively on shopping. In contrast, Amazon’s Inspire only has content to drive shopping. That makes it significantly less engaging than competing apps. Amazon’s new shopping feature is TikTok-like only on the surface; without content, it doesn’t compare.

Amazon already tried launching social networks - like Spark in 2017, which went nowhere. When announced, Amazon described it almost exactly as Inspire today, “When customers first visit Spark, they select at least five interests they’d like to follow and we’ll create a feed of relevant content contributed by others. Customers shop their feed by tapping on product links or photos with the shopping bag icon.”

Social apps are ahead in the commerce race with Amazon. Practically all have launched some version of e-commerce functionality, even if ads still define all of their commerce. Amazon is catching up, but social features are a unique challenge, which, even given Amazon’s excellence in other fields, will be very hard. Social commerce is a competition for attention, and that’s where Amazon will face the biggest hurdle - stealing it from TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram.