Shopify’s most significant opportunity is a marketplace. It already helps with data, payments, fulfillment, capital, and store management. It helps with everything except for one thing - finding customers. As customer acquisition costs rise, Shopify’s challenge is to help here too.

In 2019, $61.10 billion worth of products were sold through Shopify worldwide. In the U.S., if Shopify merchants were grouped into one, they would represent the second-largest online retailer, second only to Amazon. It grew to this size enabled by the partner ecosystem and by solving most of the challenges for brands on the supply side.

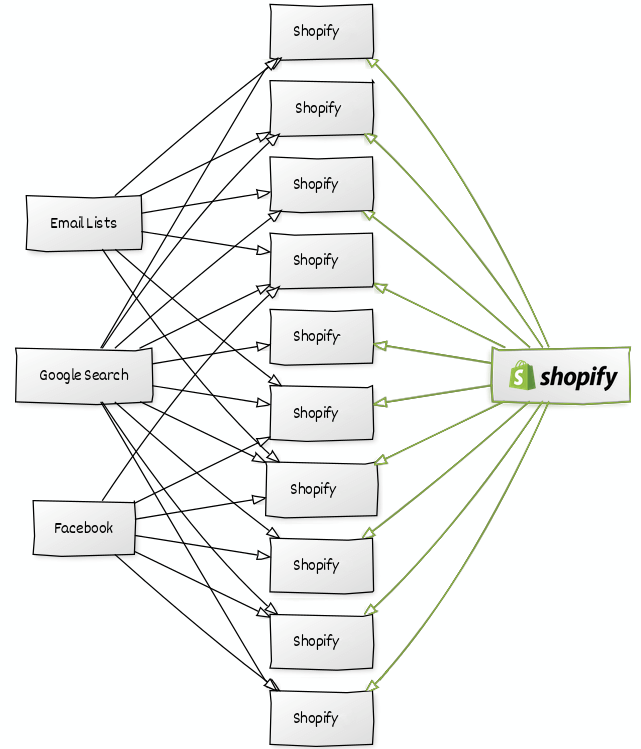

Today, brands drive traffic to their Shopify stores from their email lists, social followings, and, at increasing costs, advertising on Google and Facebook. Without any of this going away, Shopify could be an additional source of shoppers by curating its more than a million merchants into a marketplace.

Many marketplaces get built by following the “Standalone Mode” or “Single Player Mode” strategy. In their early stages, “a user should be able to derive value out of the product even when other users aren’t on it,” described Sangeet Paul Choudary. This works for two-sided marketplaces where one side needs to be brought on board before the other side can see value in the marketplace.

The restaurant reservation company OpenTable followed this approach, for example. Simplified, it first provided booking management and point-of-sale software, which restaurants could use to manage their operations better. Then, once enough restaurants were on board, they launched a customer-facing website to bring new customers to those same restaurants.

Shopify could do the same. Structurally it has all the building blocks to turn on a marketplace. It has been operating in standalone mode for over a decade and thus could launch a shopping website to bring new customers to more brands without stopping the existing offering from working.

Google is one of the primary sources of traffic for Shopify stores. It acts as a basic marketplace by linking customers to stores based on searches. The internet as a whole would benefit from reduced reliance on Google as the central point of discovery, and Shopify being its own Google is one of the ways that could happen.

Lastly, many more companies are providing the tools Shopify has to build online stores. But Shopify’s targets shouldn’t be set on competing with those. Instead, it should be thinking bigger. Software for online stores will come and go, but none of it will challenge Amazon for market share. And yet they could, were they to figure out the demand side.

There is a Prada store northwest of Valentine, Texas, just off U.S. Highway 90. It’s a fake store for the Italian luxury fashion house; it is a permanent sculptural art installation. But were it a real store, these are the type of stores Shopify allows its merchants to launch.

Any new Shopify store is in the middle of nowhere in a desert on the internet, and it’s up to the brand to make people come to it. In the case of Prada, people do. For many smaller brands, there aren’t enough Facebook ads they could buy to make people take the trip.

Amazon, on the other hand, is a super mall in downtown New York City with hundreds of millions of visitors a day. Opening a store there still puts the brand on the 177th floor in the maze of infinite corridors, but if the brand spends on advertising and grows sales, as well as get reviews, more people discover the store.

Shopify has made it very easy to start selling online, but it has distanced itself from those stores, remaining the company behind the scenes. This should change, although it doesn’t need to be the same format as search-based marketplaces like Amazon.

In the battle against Amazon, Shopify’s opportunity is not better fulfillment options or more tools. It’s the ability to use their sheer size to drive down customer acquisition costs for small brands, thus enabling them to grow faster and more efficient, which would, in turn, expand the overall ecosystem.